George Washington defeated the Newburgh Conspiracy by seeming tired, and the performance tells us about the history of American military culture in ways that speak to our own cultural pivot into drag queen recruiting videos.

The American Revolution ended in 1781 at the Battle of Yorktown, but it ended ended in 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was finally signed. That meant two years when the war was over but the war wasn’t over, and the Americans held their army in camp — near Newburgh, New York — as insurance against failed negotiations. Meanwhile, the men held for two years of very dull service had been treated poorly throughout the entire course of the war, sometimes being paid and supplied but more often not. Some were nearing personal ruin, burdened with debt from unpaid service and families abandoned for years on struggling farms. (See also.)

So a group of Continental Army officers wrote to the Continental Congress in 1782 with a two-part warning about pay and postwar pensions: First, maybe they’d just give up and go home without waiting for a successful treaty, leaving the country unprotected; but second, maybe they wouldn’t disband when the treaty came back, remaining at the head of a large group of armed men in a new nation with weak institutions. Not a subtle hint, that last part. The army had suffered mistreatment, they wrote, and “any further experiments on their patience may have fatal effects.” My bet is that most Americans don’t know the officer corps of the Continental Army plotted to execute a military coup, or at least gestured at being willing to.

Making a threat, the officers worked in camp to rally other officers to their cause and make the threat credible. An anonymous letter circulated, telling men that their new nation was sending them a message with its conduct: “Go, starve, and be forgotten!” The officers called a meeting to discuss their next moves against a government that was treating them with scandalous neglect.

Washington showed up. Uninvited, unexpected, he walked in and asked to speak. He’d prepared some written comments, and he read them to the assembled officers. But one of the things he said isn’t preserved in this handwritten document, because he added a gesture that wasn’t on the page, reported later by men who had seen it: He struggled to read the document, and pulled out his reading glasses — weakly, with his hand shaking. And he said, quietly, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in the service of my country.”

It’s not like a clerk was taking minutes at the criminal conspiracy, but later accounts suggest that men gasped and sobbed, overcome with shame. Of course you've suffered, Washington was telling them, and of course you’ve sacrificed, and of course people who haven’t been at your side through the trial don’t understand what you’ve done. He showed them: Their leader wore down his body without complaint, demonstrating forbearance and self-abnegation while serving in a profession of honor. He had grown almost blind in the service of his country, but he continued to serve. He was, what word am I looking for, a soldier.

I spent a few years working in the disciplinary archives of the early national New England militia, a project I loved and a dissertation committee tolerated, and I found this message of disciplined self-abnegation everywhere. Men who maintained control of their passions and their appetites were respected; men who didn’t, weren’t. I can give examples well beyond the boundaries of human patience, so let’s see if we can wrap this up quickly.

David Whitney was a major general of the Vermont militia in 1799 when he beat his wife — “and in the most base and mean manner, debauched the wife of his friend, and thereby destroyed the peace and happiness of a respectable family.” His subordinates filed a complaint with the governor, calling his behavior “unmilitary” despite the fact that it had no military context. A court-martial convicted him and “broke” him — they took his rank and forbade him from holding a military commission, a sentence the governor approved. To the other officers of the Vermont militia, a man who lacked self-control couldn’t be a military officer; what he did in his house, or in his friend’s bedroom, showed that he didn’t merit his rank. (I briefly mentioned David Whitney in an earlier post.) So:

He was ruled by his passions and appetites

Therefore, he wasn’t a soldier

Same argument, different context: The Newport Artillery was an independent military company, but served under the authority of the governor of Rhode Island. At least one officer of the Newport Artillery was tried by a court-martial made up of officers from the standing militia of the state, but the company privately held its own special trial for a particularly disturbing event — something they had no authority to do.

In 1814, during a war, the Newport Artillery garrisoned Fort Greene. In October, a sergeant there told Pvt. Richard Hazard Jr. that he had violated military regulations and was under arrest. In response, Hazard “loaded a gun primed and cocked it; and declared he would shoot the sergeant; and when in the act of taking aim, the gun was wrested from him.” In wartime, raising a weapon against an NCO could have led to Hazard’s execution, but the Newport Artillery declined to report the event outside the ranks of the company. Instead, they held a “court of inquiry,” and the extralegal court sentenced Hazard to expulsion from the company. "And further," they added, "that it be recommended to the Members of the company, not to associate with the said Richard Hazard junr.”1 They sentenced him to a local kind of social death: He would be ignored in the streets of Newport. He was ruled by his passions and appetites, so he wasn’t a soldier, and he wasn’t a social equal of other gentlemen.

Now: My first team leader, on my first night at a duty station as an infantryman following basic training, told me to be ready for a “team-building exercise” after dinner, and it was a night at the Lucky Seven lounge on Victory Drive, where we played pool with strippers. Let us not pretend that the infantry, for example, is defined by its aversion to sex and alcohol. But there’s a frame; the prevailing ethic has usually been some version of “do what you feel, but handle your shit.” Using the language of first sergeants, everything after Friday afternoon is yours, but in Monday morning formation, “I shouldn’t be able to smell how you spent the weekend.” In the long-prevailing military culture you get wild within boundaries, and you know when to switch it off.

So the transition to this:

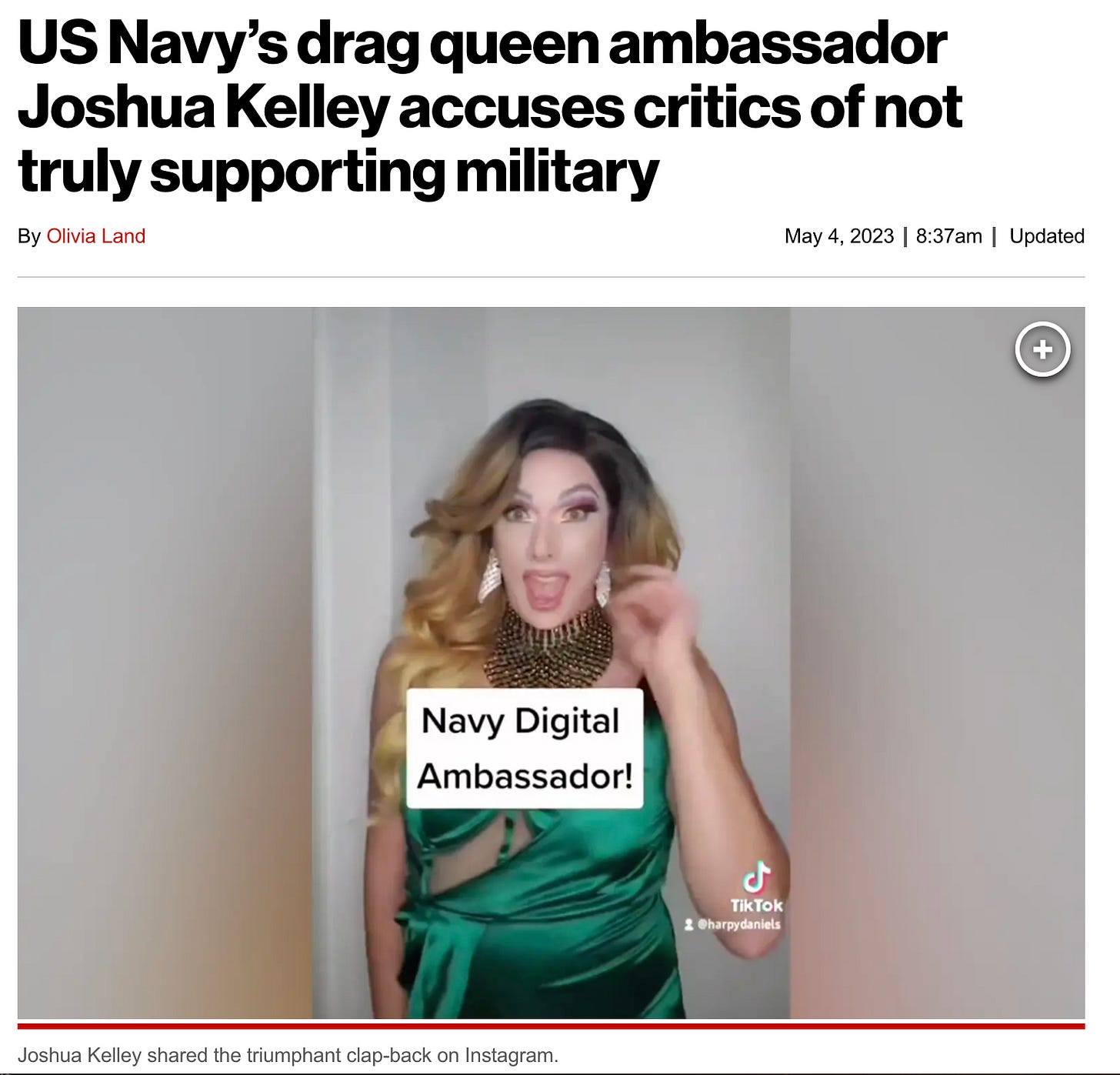

…in which the Navy, as an institution, sponsors and foregrounds a sailor’s sexual identity, strikes me as not just a deviation from normal practices, but rather as a departure from an entire set of foundational cultural presumptions. Your private self isn’t military; it exists, but it exists outside that frame. So the New York Post tell us that the Navy’s nonbinary drag queen is clapping back at the haters:

….and I’m trying to imagine myself sitting my first sergeant down to brief him in full on my sexual identity. (“That’s interesting, private,” he says. “Let me get the sergeant major in here to hear all the details.”) The point at the moment isn’t that this petty officer is gay, or nonbinary, or a drag queen. Stop and imagine the US Navy officially sponsoring a new recruiting influencer, Petty Officer Chad, who works up a bunch of TikTok videos about wrecking hot chicks down at the club so you can see what it’s like to be in the military. The New York Post, continuing:

The active-duty non-binary drag queen who served as a digital ambassador for the US Navy hit back at critics Wednesday — accusing them of only supporting the military when it “benefits” them, while defiantly declaring “you don’t scare me.”

Yeoman 2nd Class Joshua Kelley, whose drag name is Harpy Daniels, responded to the widespread fury about their appointment, led by Army veteran Graham Allen and decorated Navy SEAL veteran Robert J. O’Neill, on social media.

In a video posted to TikTok and Instagram, Kelley can be seen alternating between their military uniform and drag looks while declaring that they “DGAF” about backlash.

Alternating between their military uniform and drag looks: that is, associating the military uniform with drag, public identity with private identity. It’s an erasure of competing frames, and it’s a rejection of the cultural expectation that military identity is primarily formed around the acceptance of restraint, control of the appetites, and self-abnegation.

The thing I see in our historical moment, over and over again, is the growing habit of institutions to focus on things that fall outside of their purpose, which grows around the decay of cultural norms. Go back to the top: George Washington wore down his body without complaint, demonstrating forbearance and self-abnegation while serving in a profession of honor, and he carefully displayed that performance of values.

Compare this to an officially sponsored drag queen petty officer publicly clapping back at critics. How does that work?

At the incredibly pleasant Newport Historical Society, see "Records, Newport Artillery, Vol. 2: 1794-1825," entry of Oct. 20, 1814. The sergeant’s name is also interesting: Sgt. Hazard.

I love that story about Washington. I used it when I taught history. It says so much about service and sacrifice.

Today's military: What can I say? I retired in 2005, when it was still "Don't ask, don't tell." Today it seems like it's "Do ask, tell all." And so I guess I'm now officially old and crotchety.

But George Washington was white privilege, or something.