Decoupling Strategy: Distributed Irritation

in which history tells you to be a pill and roll your eyes

How a thing that everyone has to do becomes a thing that no one does.

In the second Militia Act of 1792, Congress defined a uniform militia in all of the states:

That each and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States, resident therein, who is or shall be of age of eighteen years, and under the age of forty-five years (except as is herein after excepted) shall severally and respectively be enrolled in the militia… That every citizen, so enrolled and notified, shall, within six months thereafter, provide himself with a good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch, with a box therein, to contain not less than twenty four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball… and shall appear so armed, accoutred and provided, when called out to exercise or into service, except, that when called out on company days to exercise only, he may appear without a knapsack.

So, by federal law, every military-age white male in the country (except men who were exempted by the states, like clergymen) had to report to the local militia commander to be enrolled in their local company, and had to own a long list of equipment, and had to show up to train with that equipment when ordered.

They mostly didn’t. For decades, states reported their militia enrollment to the War Department, and it sometimes appeared that some states, by trying really hard, sometimes almost made it to something in the neighborhood of half participation. In 1826, the Barbour Board — named after Secretary of War James Barbour — evaluated the unmistakable failure of the federally defined uniform militia, and suggested trying again with a smaller group of select militiamen. The board’s report was universally ignored, because by 1826 the federal government, like, couldn’t even: Everyone knew the model of widely shared militia service had failed.

Historians have usually described the failure of universal white male militia service in the early republic as a top-down policy blunder in which political leaders didn’t try hard enough to make the thing work. But a marginal historian named Chris Bray, in a dissertation that generated no excitement of any kind in academia, argued that the universal white male militia obligation was doomed by something else: widespread irritation and popular resistance. The militia obligation reached into the lives of militiamen in ways they didn’t expect and wouldn’t tolerate, so they stopped showing up.

There are many different ways to tell this story, but let’s do it quickly.

Most surprisingly, militia officers were brought before state military courts for non-military political speech. An officer of the Maryland militia offered a toast at a private dinner that offended other guests, so he was brought before a court of inquiry. The future congressman Robert B. Cranston, leading a band at a political reception for the governor of Rhode Island, chose music that the governor found insulting; he had Cranston, a captain in the Newport Artillery, tried by a court-martial. Officers brought before military courts for private speech in non-military settings came to court fighting mad, and printers distributed the transcripts of the proceedings so other men could see what had been done to them.

The role of state military courts kept creeping outward, taking in sexual behavior and general strangeness; in 1798, a state court-martial in Vermont tried Major General David Whitney over charges that, among other things, he liked to have sex with other men’s wives. (Well of course, Whitney told the court, but how is that a military offense?) You can find a discussion of that one starting on pg. 167 of this document, if you’re having a slow day and are desperate enough for entertainment.

Meanwhile, militiamen in the ranks were subject to fines for failure to appear, which they spent considerable time contesting, and in some cases had personal property taken by force to satisfy their military penalties. And they were shocked to discover how much control militia officers had over their bodies. In Connecticut in 1811, a private tried to get out of training by arguing that he had a painful testicular injury; his company commander insisted on performing a personal inspection of the testicles in question before adjudicating the matter of a training release, leading one of his lieutenants to pronounce him the “Bollocks Master General” of the state militia. (The lieutenant was court-martialed, which is the opening story of the first chapter of this book.)

Militiamen were treated like property — and like subordinates in their own towns — and sometimes made subject to military authority far beyond the obligation to show up at training events a few days a year.

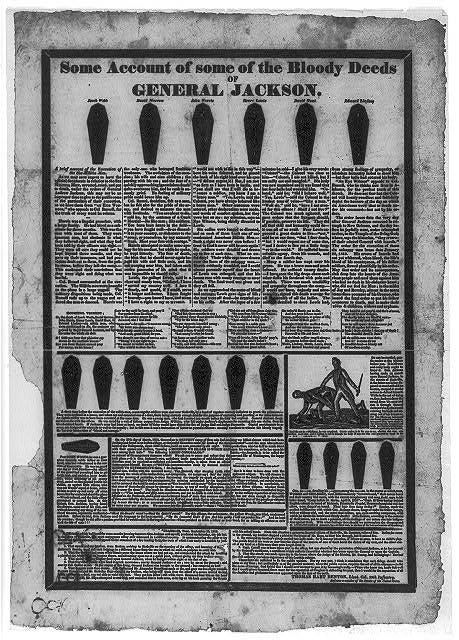

Finally, two of the most famous political controversies involving the militia of the early republic turned men against the institution they were expected to serve. In 1814, Tennessee militiamen called to active duty to fight under Andrew Jackson’s federal command in the Creek War reached three months of service and left, arguing that they’d done as much duty as militiamen could be forced to do; Jackson had six of them shot as an example to the others, a choice that became a political controversy when he ran for president. The same year, wanting to invade Canada, President James Madison proposed the use of state militia rolls for federal conscription — taking men from their companies and placing them under the command of regular army officers. That proposal led to the Hartford Convention, where delegates from New England states discussed the possibility of secession in the face of such a dire insult.

So: In 1792, Congress passed a law saying that every white male between the ages of eighteen and forty-five could have his testicles examined by a neighbor before being shipped to a war in Canada for no good reason, and by the way we might shoot you. You can see why this was such a popular institution.

This brings us to poor Thomas Mayhew.

By 1824, the men of Heath, Massachusetts, had entirely abandoned their duty to train in the militia. So the state disbanded the town’s militia company, and ordered the men of Heath to train with the companies of their neighboring towns — where they also didn’t bother to show up. So Mayhew, who commanded what was left of the militia in the neighboring town of Charlemont, sent his clerk to Heath to gather the names of the men who were subject to military duty.

The clerk returned with the information that no one in Heath knew the names of even one man anywhere in the town — it was just a whole community where no one knew anyone, even their immediate neighbors. The clerk did manage to track down a man named Rugg who was rumored to have once been a militia sergeant, but Mr. Rugg had suffered from a significant loss of memory that made it impossible for him to say if the town had ever maintained militia rolls, or had ever had anything to do with the militia. The clerk was invited to depart.

Ordered to by God get the names of Heath’s military-age men or face a court-martial, Mayhew happily accepted his court-martial, and Heath wasn’t bothered again. The men of Heath, Massachusetts, repealed the Militia Act by aggressively doing nothing at all.

There was no movement to do any of this, no national association that lobbied legislatures. There was no anti-militia-duty leader; there was no resistance literature. People just…stopped.

This is an example that remains available for use, should it ever be needed.

Will be offline more often than not for a few days.

Mockery is also an excellent way to disarm a narcissistic psychopath Globalist.