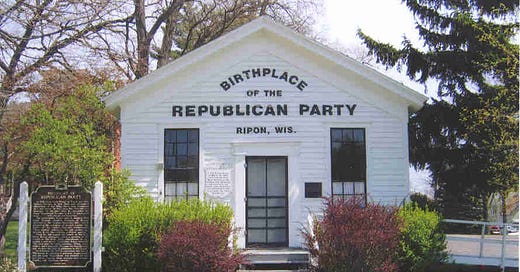

In 1854, Whig Party members disgusted by their party’s weak opposition to the westward expansion of slavery founded the Republican Party. Two years later, the new party ran its first presidential candidate, John C. Fremont, behind the slogan that appears at the bottom of these campaign rally-song lyrics:

Free Speech, Free Press, Free Soil, Free Men, Fremont!

The reason free speech and a free press were in there as political premises in 1856, as contested values a new political party was fighting for….

Okay, hold on a minute. In 2022, we’re a little baffled that we’re fighting for free speech. An army of sniveling shitweasels insists that we need guardrails around our discourse to prevent extremism, and Twitter employees gasp and sob as some horrible monster threatens to use their platform to let people just say stuff.

Stop trying to let people speak freely, you Nazis!

The whole thing is so baffling because we feel like the other side is trying to win the game as we amble out of the locker room and get on the team bus to head back to the hotel, like, game’s over, folks, we won an hour ago. Aren’t these long-settled questions? How is it that people are trying to drive us back against the powerful course of the American free speech tradition?

And one argument I’d like to offer, if Robert Reich will allow me to make it HITLER HITLER HITLER this content should be moderated out of existence to protect democracy, is that the argument we’re hearing right now is very much one of the American traditions regarding political speech. We buried it for a long time, but it’s real, it has been quite powerful, and it’s back.

Max Fucking Boot, my God.

But the legal scholar Michael Curtis argues, in an important book about the history of free speech in America, that a “bad tendency doctrine” had considerable power from the early republic into the 20th century. “By this approach,” he writes, “speech that might cause harm in the long run could be suppressed.”1

There are other examples (and here’s another one for dessert), but the center of that suppression over potential future harms was slavery. In a context of growing political tension, Southern states suppressed the everloving shit out of anti-slavery discourse in the 1840s and 1850s — after an earlier openness to debate about the meaning and future of the institution. People in Southern states were arrested and imprisoned for possessing anti-slavery literature; postmaster was an important patronage job for political machines because they controlled the mail, and decided what to deliver, and your abolitionist bullshit ain’t it, son.

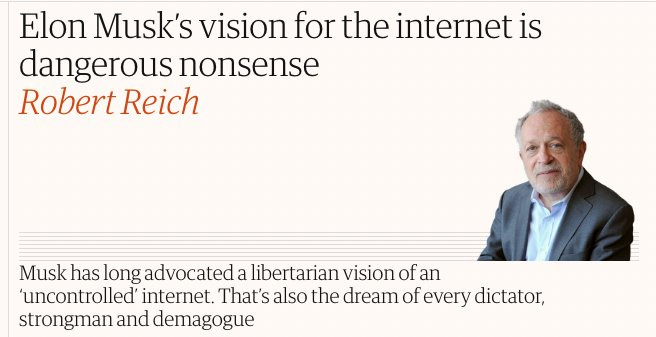

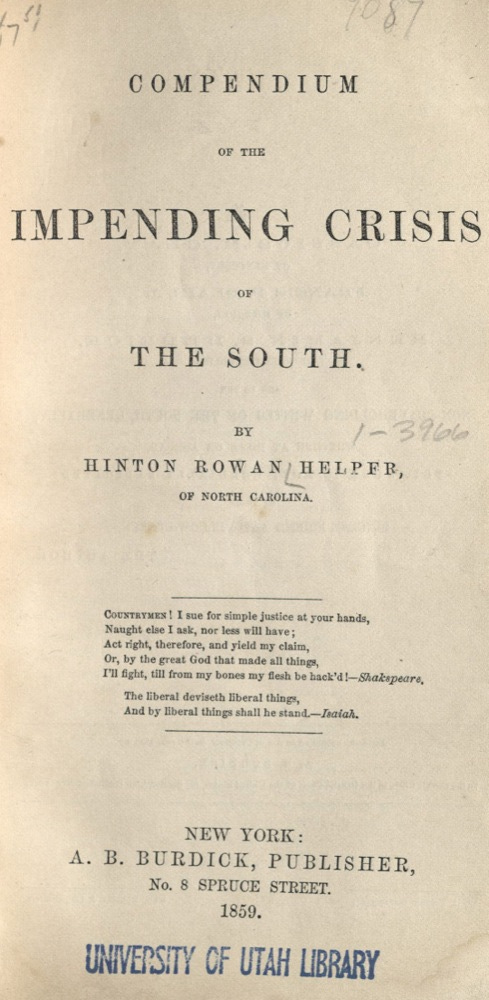

One of the clearest moments, when slaveholders and their advocates sounded most like Max Fucking Boot2, came after Fremont’s defeat on a free speech / free soil platform. In 1857, the occasional North Carolina resident Hinton Rowan Helper published an attack on slaveholding that was meant as a political appeal to Southern whites who didn’t own slaves — an attack from within. As Curtis writes, “Helper sought to prove, with assistance from census data, that the South had become an economic disaster area because of slavery.” Republicans distributed an abbreviated “compendium” of the book as campaign material:

Southerners, feeling that Helper’s words were violence, moderated his content. A North Carolina minister, Daniel Worth, “preached against slavery in Guilford and Randolph counties, sold copies of Helper’s book and the Republican New York Tribune, and worked to convert people to the antislavery cause.” He was arrested by the Guilford County sheriff, convicted — for the crime of distributing an incendiary book — and sentenced to prison. See, they put guardrails on our discourse.

In 1859, John Brown led his raid on the armory at Harper’s Ferry, and Democrats pounced. Aha, they said, Republicans distributed Hinton Rowan Helper’s antislavery book, and then the inherent violence of that argument led to insurrection. Widening the discussion to bring in other examples, Senator Albert G. Brown of Mississippi argued that the suppression of antislavery literature and speech was necessary because of the potential consequences:

I have no hesitation in saying that I would not myself tolerate any man who would go to my State and avow his preference for the election of Mr. Seward upon the programme laid down in his Rochester speech, which I understand to be an announcement that there is an irrepressible conflict between the North and the South, and that we are to be all free States or all slave States, which I will say, without arguing the question, can mean nothing else than that slavery is to be blotted out. No man would be permitted to teach that doctrine in the country from which I come, because that doctrine carried out to its legitimate logical conclusion amounts simply to the emancipation of the whole negro race in the southern States. No such doctrine would be allowed to be taught there, because our safety, our domestic quietude, our peace, the peace of our hearths, depends upon the repression of such doctrines with us.

No man would be permitted to teach that doctrine, because our domestic quietude depends upon repression.

This is in us; it’s part of our national DNA.

In that context, it’s less surprising to find the idea of repression for the cause of safety climbing out of its grave.

If you’re interested in this, here’s a law review article from 1981 (link is to a PDF file) that covers bad tendency doctrine and the 19th-century suppression of political speech. Or you can buy this book straight from the Duke University Press, though the price is a little precious.

(spits on the ground)

The same people do the same things, over and over and over. You'd think we'd start writing things down so we could learn from the experience.

You had me at "sniveling shitweasels" I laughed so loud and hard in this cafe.

Yes. That.

Let's suppress free speech, censor the internet, censor anything and everything actually (because feelings!) for our democracy and safety! It's insanity. Truly.