In 1973, armed members of the American Indian Movement, alleging broken treaties and tribal corruption, seized the symbolically meaningful village of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. But there was a post office there, so a team of postal inspectors went to check on the security of the building. They were immediately taken at gunpoint and marched away into captivity. As a later court document would put it, “They were then informed by co-defendant Leonard Crow Dog that they were prisoners of war and would be treated as such.” Federal spies entering native land, the AIM leader Russell Means soon added for the benefit of visiting reporters, would be “shot by a firing squad.” It was, for the moment, a piece of political performance; the postal inspectors were released a couple hours later, minus their government-issued revolvers. The stand-off between AIM and the federal government, with repeated gunfights, went on for a total of 71 days; a federal law enforcement website still describes it as “the longest civil disorder in the history of the Marshals Service.”

Among the many remarkable claims Joe Biden made during his idiotic Red Speech, this one has stuck with me: America, he said, is a nation…

“…that rejects violence as a political tool.” Says the guy who was VP to a POTUS who allegedly started his political career with a fundraiser at the home of the Weather Underground leaders Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, before “vastly expanding and normalizing the use of armed drones for counterterrorism and close air support operations in non-battlefield settings—namely Yemen, Pakistan, and Somalia.” Nope, no violence here. We just don’t put up with that stuff.

It’s hard to exaggerate this point: Violence has been one of America’s most important political tools, and the realities of the past suggest the likely realities of the future. This isn’t advocacy — it’s description. We have 400 years of frequent and serious political violence behind us. Spend a few moments with the seven-page table of contents for Richard Hofstadter’s 1970 anthology American Violence: A Documentary History. Sample section:

Conflict between government and citizens over unaddressed grievances has led to violent responses over and over again: Bacon’s Rebellion, the Regulator Movement, the Green Mountain Boys, Shays’s Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion, Fries’s Rebellion, and the single-entry honorable mention category of the Dorr Rebellion, about which we can only say that hey, at least they tried.

The country was born in violence — and then it settled a subsequent contest between incompatible systems of labor, slave and free, with violence.

And then Reconstruction, the federal effort to settle the Civil War and set the South on its post-emancipation political course, ended in violence. Rising politicians used violence to make their reputations: “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman became a governor and a U.S. Senator in part because of, not despite, his role in the Hamburg Massacre.

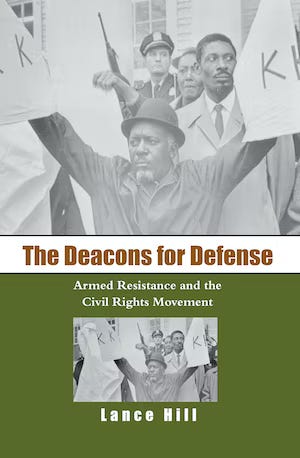

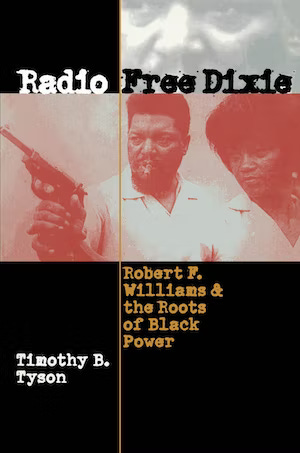

And then, to keep going on the same timeline, the Jim Crow system that followed the death of Reconstruction ended in good part because of violence, or at least because of the possibility of violence being used as a political weapon — because armed self-defense was the backbone of the Civil Rights Movement, a movement that supposedly represents a victory for non-violence. Note the title the leader of the NAACP branch in Monroe, North Carolina gave to his memoirs: Negroes With Guns.

Meanwhile, battles over producerist ideology and the rural-urban divide were casually and frequently violent, and — for example — farmers prevented Depression-era agricultural foreclosures by beating the hell out of sheriffs and judges. One of those judges, Charles C. Bradley of Iowa, was dragged out of his courtroom and shoved into the back of a truck. “Carried to a crossroads a mile outside of Le Mars,” a history of midwestern farm rebellion says, “his trousers were removed and he was threatened with mutilation. A rope was thrown across a roadside sign and pulled tight around the judge’s neck as the mob demanded that he swear to authorize no more foreclosures…A hubcap full of grease was dumped on the judge’s head, his trousers, filled with gravel, were thrown into a ditch and the mob departed, leaving the judge besmirched and nearly unconscious in the road.” (The governor soon called out the National Guard, but the local Iowa National Guard units were mostly made up of the sons of the farmers, so.)

Or pick your moment. Nativist violence in California. The battle between striking steelworkers and Pinkertons at Fort Frick. The Zoot Suit riots. No, America isn’t a nation that rejects violence as a political tool. We’ve kept that tool within arm’s reach for quite a while.

The obvious strategy to aggressively and relentlessly other tens of millions of people — these MAGA extremists, whose existence is incompatible with our system of government — exhibits an astonishing historical deafness, as does the increasingly naked effort to use the federal criminal justice system against political enemies.

You can provoke violence in America. It works. You’d have to be an idiot to do it, but as it happens….

The Red Sermon really did seem like a deliberate provocation. Along with a lot else they've done. The other possibility is that they're so insanely overconfident, so charged up with blind hubris, that they think they can continue poking indefinitely without provoking an explosive response when patience gets exceeded. Then again, they'd dearly love to have an excuse to take their secret police and riot mobs fully off the leash, so it's very possible they know exactly what they're doing.

Thanks for the backgrounder showing many instances of political violence in America. Common denominator is The People responding to governmental overreach. And boy howdy is our gov't reachin' over these days. Not even a reach around.