There’s an easy layer here and a harder layer, but let’s get through the easy one so the hard one makes sense. Look for the hole in the bottom of the coffin.

Once again, Donald Trump is supposedly doing something shocking and unprecedented, proposing to remake the leadership ranks of the American military to make the armed forces align with his policy objectives. Oh no, the news media has explained, running around in circles with their hair on fire.

Inevitably, the stories are worst-evering and claiming that it’s unprecedented for a new President of the United States to force policy and personnel changes on the military, which is an “overtly political” insertion of partisanship into the apolitical armed forces. Sample claim, from the Politico story above:

“Hegseth is undoubtedly the least qualified nominee for SecDef in American history. And the most overtly political. Brace yourself, America,” Paul Rieckhoff, founder of Independent Veterans of America, said in a post on X Tuesday night.

Similarly, congressional bad-faith actor Elissa Slotkin, a former CIA officer, warned recently that Trump risks “politicizing” the military, which has traditionally been free of politics:

This is false. A couple centuries of it. There’s a kind of very limited truth to some of it — the tradition is for military officers to stay out of partisan politics while in uniform — but the military is political, and always has been. The use of military force is political. The implied potential for the use of state violence is necessarily political. And so the shaping of military personnel and policy is absolutely, inevitably, inescapably political, and always has been.

Start here, with a book that I very much hope the the Trump administration’s soon-to-start-work DOD political appointees all read in the next two months:

My goodness, the political and social reform of the military establishment between 1801 and 1809? But that’s UNPRECEDENTED, right? TRUMP TRUMP TRUMP, confused noises, brain injury from watching CNN.

Jefferson was the third president, and the first president who wasn’t a Federalist. His election was the “Revolution of 1800,” a dramatic break with the political assumptions of the early republic: the power of the Federalist establishment wasn’t inevitable. He inherited a Federalist-led, Federalist-oriented army, in the immediate aftermath of a crisis of political repression in which Federalists had shut down newspapers and arrested their critics. During the Adams administration, Alexander Hamilton had worked carefully and persistently to make the federal army more plainly Federalist — he had politicized it. He meant to.

Senior Federalist military officers were the veterans of, or the sons of the veterans of, the officers of the Continental Army, in a moment when the former officers of the Continental Army were joined together in the Society of the Cincinnati. Significantly, they formed that elite private club at Newburgh, New York, in 1783 — so it was born next to the Newburgh Conspiracy, a semi-serious threat to overthrow an inept government and implement rule by military officers. And the founders of the Society of the Cincinnati made membership hereditary, descending to firstborn sons. So the army was run by an elite corps of men who very much regarded themselves as elite, who had already threatened the stability of the government, and who explicitly intended to pass their elite status down to their oldest sons and then to their oldest sons, like European aristocrats.

Imagine all of that at the same time, in the years of a post-revolutionary settlement. Jefferson found a Federalist-commanded army threatening, and not hyperbolically.

So he made it bigger. He streamlined the organization, moderately reducing the ranks of senior leaders, but also adding new junior officers in a growing force. He diluted the Federalist presence in an expanding officer corps. And he founded a new military academy at West Point, New York, to train those new officers with a professional and depoliticized ethic. More officers made Federalist officers less powerful.

He also set his Secretary of War, James Wilkinson — a colorful figure who may have committed a little light treason — to the task of reducing the Federalist culture of the officer corps. High Federalist officers still wore the queue, the braided and powdered ponytail of an earlier generation, and it very much marked them as Federalists in uniform, so Wilkinson ordered them to cut it off. One, Colonel Thomas Butler, repeatedly refused, was repeatedly court-martialed, and died while facing yet another trial for disobedience. The story people told, possibly false, is that the colleagues who buried Butler carried out his final wishes, cutting a hole in the bottom of his coffin so he could be buried with his queue sticking out — to tell James Wilkinson to kiss his ass one last time. But Jefferson and his Secretary of War wouldn’t tolerate a symbol of Federalist identity in the officer corps of the army they led, and they spent years fighting against it.

So a new commander-in-chief of the armed forces, finding their leadership ranks politically hostile, reshaped the officer corps to dilute and diminish the power of uniformed leaders who were political opponents of his agenda.

That’s American history. Normal behavior. The Constitution identifies a single commander-in-chief. He commands. Similarly, Article One gives Congress the authority to “make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces,” in an inherently political process. The military is subject to political control.

There are other examples to be had. See, for example, President Dwight Eisenhower’s handling of the “Colonels’ Revolt” in the U.S. Army in 1956. Presidents shape the military to their agenda, full stop, and uniformed officers who oppose their agenda are pushed aside by superior authority.

Or see the Biden administration’s promotion of DEI as a central value in the military. The Biden administration was coloring inside the lines and respecting the tradition of an apolitical American military when they made DEI a critical priority of the armed forces, obviously, but Trump is being political by not continuing Biden’s policy preferences. See how that works? Not political:

Opposition? Political.

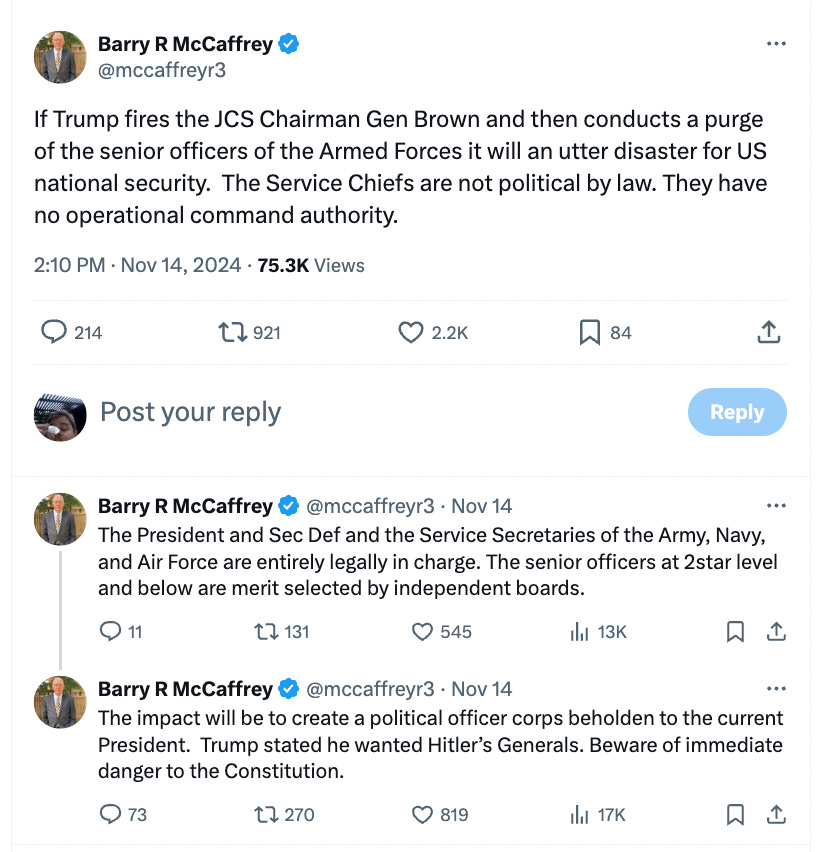

Now, the harder part. Since Gen. Mark Milley was absurdly celebrated as a hero for telling other military officers not to obey the direct orders of the President of the United States, and since a lieutenant colonel testified that the same president had made inappropriate policy choices that improperly contradicted the course set by policy staff, the horse has believed that it commands the rider. This narrative is escalating:

“The impact will be to create a political officer corps.” Oh no.

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff works for the President of the United States. He is the president’s subordinate. If the president wishes to replace him, he may. It’s well within his political authority to do so. The President of the United States doesn’t work for the military, and has no duty to remain hands-off in his relationship with organizations that he commands. The absurd headlines in the news warning that Trump and presumptive Secretary of Defense nominee Pete Hegseth are aiming for a clash with the uniformed leadership, or planning to wage war on the top brass, are a foundational misconception of the relationships between uniformed military leaders and the civilian chain of command that they answer to. The President of the United States doesn’t feud with military officers. He commands them, with legitimate and superior constitutional authority. I suspect this core principle will need to be demonstrated sometime after January 20, and demonstrated with considerable clarity and force.

It looks like Milley and his incipient junta need not only to be fired, but also to be tried in a court martial on charges of insubordination, as a lesser included charge to that of sedition as set out in Article 94 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice -

“Two types of mutiny are defined in Article 94, but both require an attempt to “usurp or override military authority.”

An individual or a group may commit mutiny by creating violence or disturbance.

Mutiny by refusing to obey orders or perform duties requires action by two or more persons in resisting “lawful military authority.” The insubordination may or may not be preconceived and does not have to be active or violent. Intent may be proven through words or interpreted through acts, omissions, or surrounding circumstances.

Sedition requires action that is resistant to civil authority. The action need not be violent nor create a disturbance.

Failure to prevent and suppress a mutiny or sedition is used when the accused did not take reasonably necessary measures appropriate to the circumstances to prevent or suppress a mutiny [or sedition].

Failure to report a mutiny or sedition occurs when the accused fails to “take all reasonable means to inform” others of an occurring sedition or mutiny. The prosecution may determine the circumstances in question would have led a reasonable person to believe mutiny or sedition was occurring; therefore, the accused failed to report. While failure to report a mutiny or sedition falls under Article 94, a failure to report an impending mutiny or sedition falls under the jurisdiction of dereliction of duty.” https://www.mymilitarylawyers.com/ucmj-article-94-mutiny-or-sedition/

“Gen. Mark Milley was absurdly celebrated as a hero for telling other military officers not to obey the direct orders of the President of the United States” - that’s the prima facie case for sedition under the UCMJ…

Swift action needs to be taken here.

Extremely informative post. Thank you for taking the time to write it.