Mark Pomerantz Revealed the Madness of the Trump Cases, While Trying to Do the Opposite

show me the man and i'll show you the crime

This book is an alarm. It’s a sign that danger is close, and that it’s serious. That’s not how the author meant it.

Mark Pomerantz published People vs. Donald Trump last year to describe his role as a special assistant district attorney in Manhattan, trying to prosecute the former president, and to complain about an initial decision in the DA’s office not to file charges. I didn’t notice it until I saw Pomerantz taking the fifth over and over again in response to recent questions about his behavior during the investigation, but I bought a copy this week — a used copy, to avoid sending money to Mark Pomerantz.

I don’t know how to begin telling you clearly enough how disturbing it is. You can despise Donald Trump and see the point. No one should be treated this way. The problem is the weapon itself, not the identity of the person it was used against.

The book opens with Pomerantz, a former federal prosecutor who went on to a long career as a criminal defense attorney, being called out of retirement to help the Manhattan DA with an ongoing investigation, the Trump case. Because the ball is already rolling when he gets there, he doesn’t describe the origins of the investigation — ever, at all. Which is a strange choice for a tell-all: Why was the DA’s office investigating Trump? What crime were they investigating? Who was the victim, and what was the complaint?

None of these questions are ever answered, in a criminal investigation that’s just assumed into being on page one, but a reader can begin to infer the answer from the absences. Pomerantz describes himself interviewing witnesses, and trying to flip potential cooperators, and endlessly sorting through Trump’s business records and tax records. But in 280 pages of detailed description, there are a few things he never does:

He never interviews a person he identifies as a victim or a complainant.

He never reviews a victim’s statement.

He never reviews a complaint that someone outside government has filed against Trump.

And then he says a couple of things that make those absences very clear.

First, he describes the prosecutor’s job as assembling a puzzle to show to a jury. You have a big bucket full of evidence, the puzzle pieces, and you have to decide how to fit them together. But usually, he adds, that job is pretty easy for a local prosecutor, because the complaint, usually delivered by the police after being taken from the victim, tells you what the crime is and organizes your work. He describes this, mixing metaphors, as “painting by the numbers.” Pages 25 and 26, if you want to read this for yourself. Because you start with the crime, knowing what it is, you build the evidence around it.

But that’s not what the Manhattan DA was doing, so their work was a lot harder. They didn’t know what they were looking for — they just knew that they were looking. On pages 13 to 15, you’ll find an outline of the many places where the DA was digging: Trump’s payment to Stormy Daniels, Trump’s taxes, Trump’s relationship with Deutsche Bank, and many other general areas of inquiry. Not crimes: “issues” and “areas of inquiry.”

They didn’t start with a suspected crime, or with a victim, or with a complaint. They started with a target, with someone they wanted to charge with something, and then went looking for something to charge him with. No one reported Trump to the police; the DA just felt like investigating him.

This office-born hunt for a crime, he says, is not unusual; when he worked for US Attorney Mary Jo White in the Southern District of New York, for example, she used to read the morning newspaper, see controversies in the news that she wanted her office to be involved in, and tell her people to go find her something. The clippings she sent down to her line prosecutors “sometimes would blossom into investigations and prosecutions.” Page 14, by the way.

So, without a complaint, without a victim, and without a crime, the district attorney’s office got started on a major investigation.

Then-DA Cy Vance was in charge, with his counsel Carey Dunne doing much of the day-to-day supervision, assisted by Chief of Investigations Chris Conroy and the director of the Major Economic Crimes Bureau, Julieta Lozano. “The day-to-day work was being done by a team of four prosecutors assigned to the Major Economic Crimes Bureau.” Then they brought in outside lawyers like Mark Pomerantz to provide full-time help, and farmed out some of the legal analysis to outside law firms. Later, Attorney General Laticia James cross-designated two deputy attorneys general as special deputy DAs to help with the case and coordinate a shared investigation.

Got that? Before they had a crime, they had a dozen or so prosecutors working on it, at least five of them full-time at first, and then at least seven. Pages 34 to 35, with the two state prosecutors joining the DA’s office on page 76.

And finally, with that large team of prosecutors working full-time on the task of finding something to pin on a chosen target, they had the leisure to test creative legal theories and novel interpretations of statutes. There’s a theme that begins to appear over and over again (DANY is District Attorney of New York County, the Manhattan DA’s office).

Page 56:

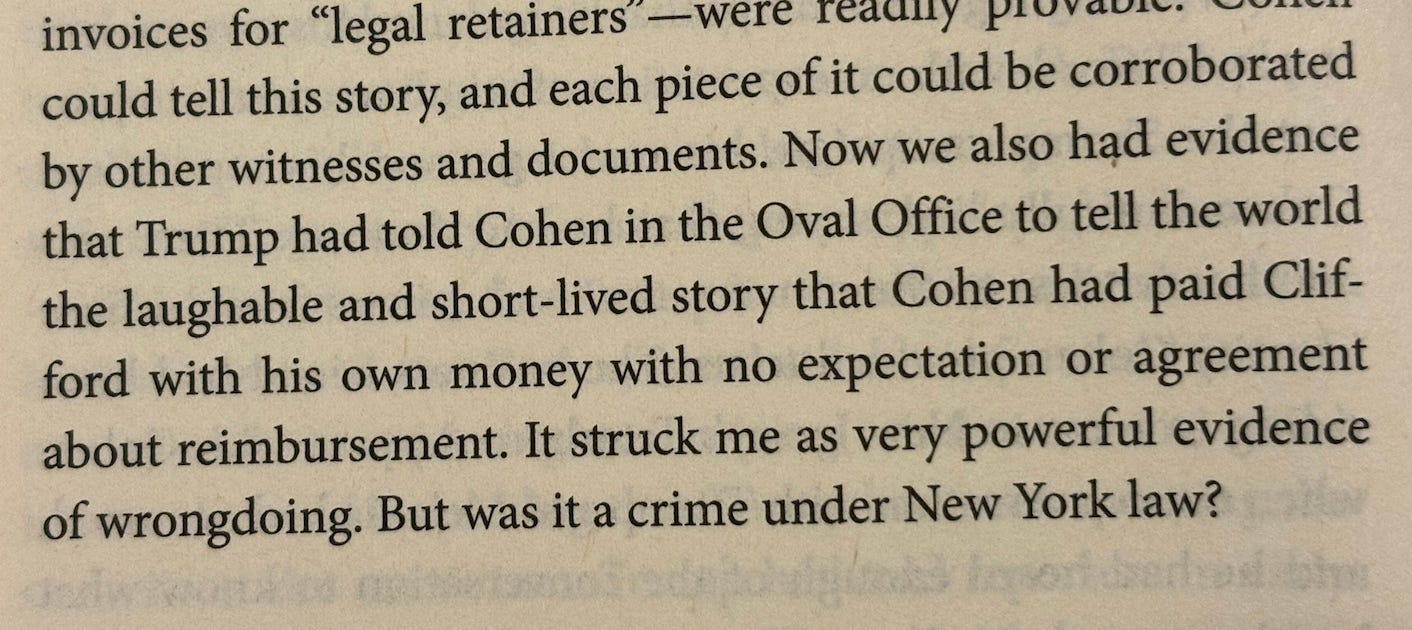

Pg. 58:

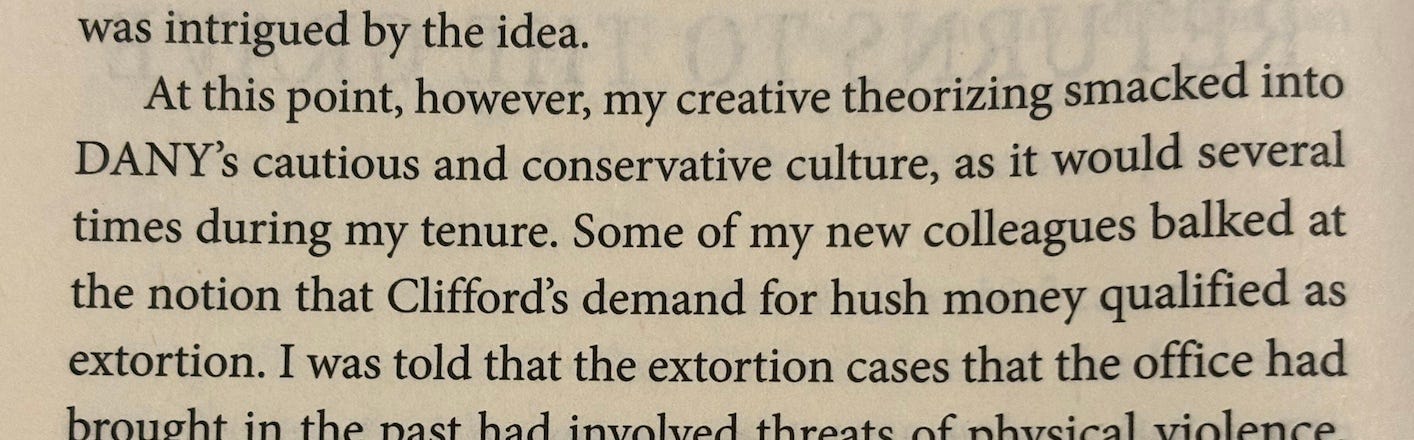

Pg. 61:

We found some stuff that seemed bad to us but it wasn’t really a crime that we could find on the books, and we applied some creative theories, but we couldn’t quite make it work because of the way the law was written, and so we tried some other stuff, and there was this one thing where the law didn’t really fit what we wanted to charge him with but, actual quote from a prosecutor, “There were possible work-arounds.” Except that, small problem, “none of the work-arounds were appealing.”

This is not a description of prosecutors who have found a crime and are trying to find the way to prove it. Flatly, this is a repeated and extremely explicit depiction of prosecutors trying to create a crime. They were cooking.

In a just absolutely astonishing passage that I can’t believe made it into print, Pomerantz says — pg. 90 — that the desire to charge Trump with a crime was being impeded by “the cultural problem within the office,” which was that the career prosecutors only liked to charge things that were “the most obvious, glaring legal violations.” In other words, they only liked to charge things that were clearly crimes, and for which there was clear evidence. Facing this very serious problem of prosecutors who hesitated to charge things that weren’t clearly criminal and provable, Pomerantz says that he told a manager in the DA’s office “about the need to refocus the team.”

He does this repeatedly, lamenting “conservative” prosecutors — temperamentally conservative, not politically — who hesitate to charge crimes when they’re not sure they can prove them. See, for example, pages 110 to 111, where he says that good prosecutors bring cases they might lose, especially when they consider “the track record of the potential defendant.” If they feel that someone is a bad person, they should just charge a weak case and hope for the best, which has the possible effect of seeing “the target held to account for misdeeds that extend well beyond the particular crime at issue.”

Put all of that together.

They start with a target, not a crime, finding a person they hope to charge with something.

Then they throw a massive team at the target, spending hundreds or thousands of hours combing through personal, business, and tax records, and interviewing potential witnesses.

Then they apply “creative theorizing” to try to extend the law beyond its obvious language.

All while considering not merely the clarity of the eventually alleged crime, and the degree to which it can be proved, but also the degree to which the target may just be a bad person who needs to be punished a bit, maybe for bad character that extends well beyond the particular crime at issue.

Do you think that Donald Trump is the only person who might ever be harmed by this kind of prosecutorial behavior? If you run a business, for example, do you think a dozen prosecutors, choosing you tomorrow morning as their full-time target and going through a lifetime of records, applying creative theorizing about which laws might be made to fit, would have trouble finding something to charge you with?

We have a cultural problem around the exercise of power, and it threatens us all. I encourage you to read this book.

More to come.

Full post on this coming soon, but a reader has reserved a bunch of very nice campsites near Medford, Oregon for June 24-27, next to the river. Save the date, if you want to come. Tom Nichols and Anne Applebaum warmly invited.

People like Pomerantz have operated as if treating the famous speech by then-attorney general and future Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson not as a warning, but a how-to guide. It was he who said that “the most dangerous power of the prosecutor” is the ability to “pick people that he thinks he should get, rather than pick cases that need to be prosecuted.” Jackson explained that, given the variety of laws on the books, “A prosecutor stands a fair chance of finding at least a technical violation of some act on the part of almost anyone.”

Democrats have decided to sacrifice higher-order values in order to engage in blatantly political selective prosecutions, and it ought to worry fair-minded people regardless of political persuasion.

https://www.euphoricrecall.net/p/the-shameful-lawfare-of-letitia-james