Endless Lazy Manipulation: Jay Bhattacharya vs. the "Mainstream"

"these strategies have always been much debated"

I’ve said one thing here over and over again, suggesting a technique to use the generally useless Google search function in a revealing way: search within a date range. Find the moment when the “mainstream” media started insisting that an idea was a bizarre and dangerous outlier — the fringe — and see what people said before that.

So. Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, an extensively cited Stanford University health policy professor with both an MD and a PhD, has been appointed by President-elect Donald Trump to lead the National Institutes of Health. This is controversial, the New York Times explains, because Bhattacharya was a fringe-dwelling critic of mass lockdowns during the pandemic, and an author of the extremely weird and scary Great Barrington Declaration:

Dr. Bhattacharya is one of three lead authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, a manifesto issued in 2020 that contended that the virus should be allowed to spread among young healthy people who were “at minimal risk of death” and could thus develop natural immunity, while prevention efforts were targeted to older people and the vulnerable.

Through a connection with a Stanford colleague, Dr. Scott Atlas, who was advising Mr. Trump during his first term, Dr. Bhattacharya presented his views to Alex M. Azar II, Mr. Trump’s health secretary. The condemnation from the public health establishment was swift. Dr. Bhattacharya and his fellow authors were promptly dismissed as cranks whose “fringe” policy prescriptions would lead to millions of unnecessary deaths.

Bhattacharya was widely condemned by the establishment and dismissed as a crank. Trump is appointing weird outsiders who hold strange ideas!

So. Do this search, or try variations on your own using similar search terms:

What did the establishment think of mass lockdowns, general restrictions on public movement, as a response to pandemics — before that question was politicized during the Covid-19 hysteria? You have a long list of choices to test that question.

Here are some of the conclusions from a 2013 article, “Lessons from the History of Quarantine, from Plague to Influenza A,” published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, a monthly journal published by the CDC:

Quarantine and other public health practices are effective and valuable ways to control communicable disease outbreaks and public anxiety, but these strategies have always been much debated, perceived as intrusive, and accompanied in every age and under all political regimes by an undercurrent of suspicion, distrust, and riots. These strategic measures have raised (and continue to raise) a variety of political, economic, social, and ethical issues (39,40). In the face of a dramatic health crisis, individual rights have often been trampled in the name of public good. The use of segregation or isolation to separate persons suspected of being infected has frequently violated the liberty of outwardly healthy persons, most often from lower classes, and ethnic and marginalized minority groups have been stigmatized and have faced discrimination. This feature, almost inherent in quarantine, traces a line of continuity from the time of plague to the 2009 influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic.

The historical perspective helps with understanding the extent to which panic, connected with social stigma and prejudice, frustrated public health efforts to control the spread of disease. During outbreaks of plague and cholera, the fear of discrimination and mandatory quarantine and isolation led the weakest social groups and minorities to escape affected areas and, thus, contribute to spreading the disease farther and faster, as occurred regularly in towns affected by deadly disease outbreaks.

General quarantine can work, but comes with a long list of serious dangers and ethical dilemmas, and can cause a breakdown in trust that leads to behaviors which “contribute to spreading the disease farther and faster.” So lockdown strategies “have always been much debated.”

Here’s an excerpt from a 2015 article on “The Politics Behind the Ebola Crisis,” from the Crisis Group Africa Report, which you can read for free if you have a JSTOR account:

Given the dangers of a break-down in public order, the inclination to enforce extreme public health measures such as mass quarantine (and be seen as doing something) can be strong, despite debatable effectiveness. Broad restrictions on population movements to control the Ebola epidemic could only be useful, however, if everyone respected the quarantine measures (nobody trying to escape, hide the sick, etc.) and contagious individuals displayed no symptoms, neither of which was the case. And while it is understandable that governments have limited means at their disposal, the danger is that harsh measures can provoke further unrest.

Imposing local quarantines to counter Ebola remains tricky, given the need to avoid provoking panic, denying services or unduly blocking commercial relations. In practical terms, it has been almost unworkable in populated areas with porous, largely artificial borders and when even openness about the number of cases has been non-existent. Restricting movement meant also severely restricting access to livelihoods, health care, food and water. Instead of facilitating identification of suspected cases, the impact was as likely to be evasion and ever greater suspicion of health-care providers, because quarantine, a health worker said, “makes people fearful, makes people flee and creates terrible conditions.”

Mass quarantine “has been almost unworkable in populated areas,” and creates the likelihood of medical evasion, while limiting access to livelihoods. It therefore has “debatable effectiveness.”

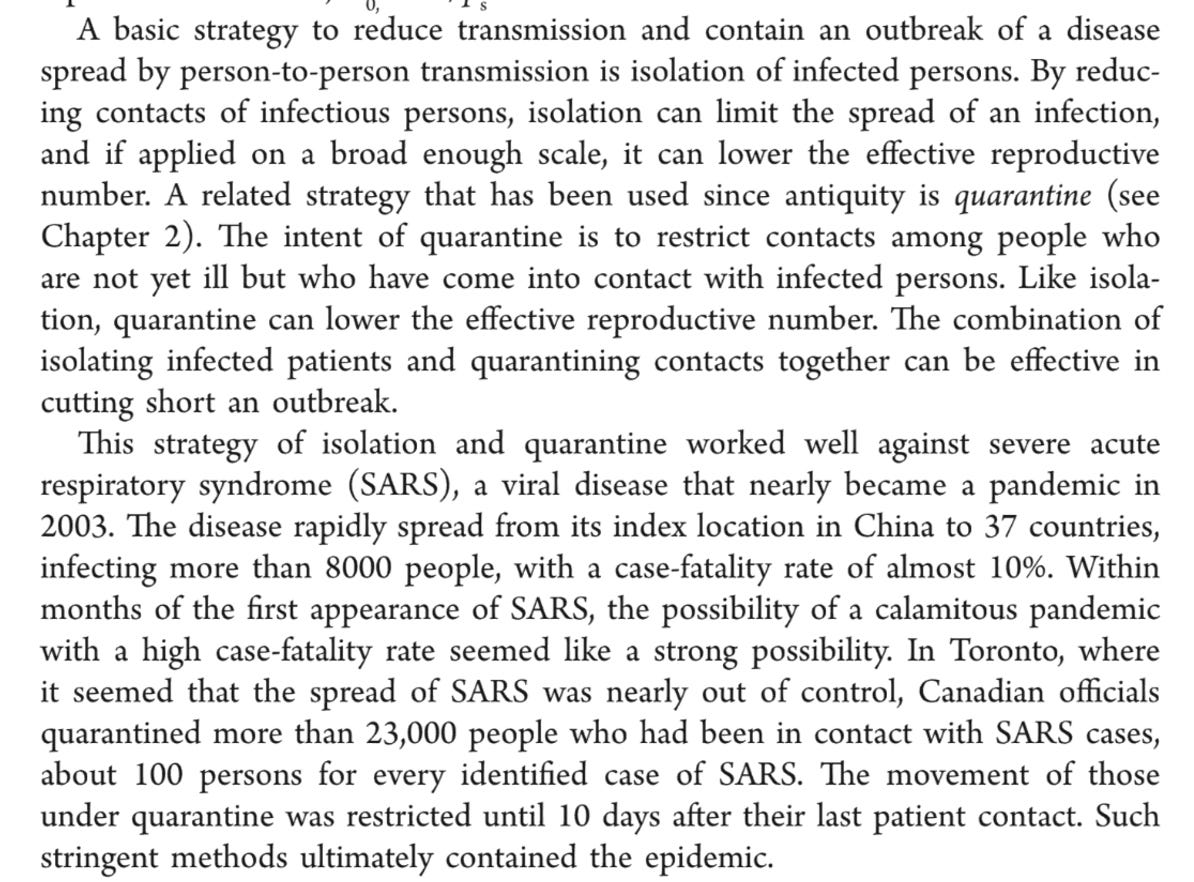

More often, the idea of quarantine was discussed, pre-Covid-19, not as the implementation of mass lockdowns, but as a measure of focused protection — limited in scope and time. This is from pg. 116 of a 2012 textbook by Kenneth J. Rothman, Epidemiology: An Introduction:

Quarantine is the restriction of the movement of people who have plainly been exposed to sick people, for 10 days or so. The idea of just locking down whole populations indefinitely wasn’t a thing.

I can go on, but I doubt there’s a need.

The authors and signatories of the Great Barrington Declaration, including Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, were the mainstream, offering arguments that reflected a widespread expert understanding of mass quarantine as a public health strategy. The “mainstream” that attacked them wasn’t. Over and over again, these framing words — mainstream, fringe, cranks — have been casually and shamelessly abused. If you doubt it, use the date range search function to test these claims yourself.

As a retired physician with some memory of prior pandemic policies, what I would like to ask the geniuses at the CDC is given the comparable mortality between Covid 19 and the usual seasonal influenza viruses, why aren't we shutting down the world every year? Also, why do they continue to fund gain of function research given the obvious dangers of accidentally(?) releasing these man-made mutants on the world? And, one last thing before I leave...why aren't we allowed to see exactly how much money our public servants in the NIH and CDC are getting individually from the IP of vaccines and other drugs funded by the public? In fact, why are the financial rewards of commercialization of their work products during their employment as civil servants not fully claimed by the public?

Jay is great but he was very wishy washy on vax injuries and problems, and so probably acceptable to Trump who is still living near a river in Egypt about the awful vaccines.