I wrote yesterday about a discussion between professional bootlicker-midwit Anne Applebaum and the historian Jefferson Cowie, a podcast on the website of The Atlantic that focused on the way mean racist white people resisted the efforts of the wonderfully benevolent federal government to protect native people and ensure their land rights during the 19th century:

Cowie: And so you have this really explosive moment where white settlers were promised, in some broad sense, access to land. They were denied it. And they took their claims of freedom against the federal government that was denying them the ability to take the land of other people—their freedom to steal land, basically.

On that evidence, Cowie concluded, the American concept of freedom is really “a very powerful ideology of domination,” centered on cruel disobedience to a persistently liberationist federal government.

I was baffled, because that’s not how any of this worked: locals trying to steal land from native people, the kind and gentle federal government trying to stop them. As I wrote yesterday, describing (among other things) the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and Andrew Jackson’s consistent policy of removal, “Flatly, the federal government was invariably the principal agent of American Indian dispossession.” But Jefferson Cowie is about as highly regarded in academia as it’s possible for a historian to be, with a long series of awards and honors and an endowed chair at a major research university. How could a well-respected historian also be someone who thinks that the federal government was trying to prevent Indian dispossession in the 1830s?

Today, with Cowie’s book on white resistance to federal authority in my hands, I can answer that question: he doesn’t. The Jefferson Cowie who appeared on a podcast with Anne Applebaum isn’t quite the Jefferson Cowie who writes books. In the discussion with Applebaum, the benevolent federal government tries to protect the Creeks against dispossession by mean local whites; in the book, federal objections to white settlement on treaty-protected Creek lands are a temporary effort by President Andrew Jackson to sustain an orderly but inevitable removal:

“Even though he was dead set on Indian removal as his eventual goal…”

The “he” in that sentence is the President of the United States, so if he was “dead set on Indian removal,” how does that prove the claim that the federal government was trying to protect Creek land rights against “white settlers” who were fighting the federal government to preserve their local “freedom to steal land?” The federal government was doing the stealing — a little more slowly than the settlers wanted. The claim in the book isn’t the claim in the podcast.

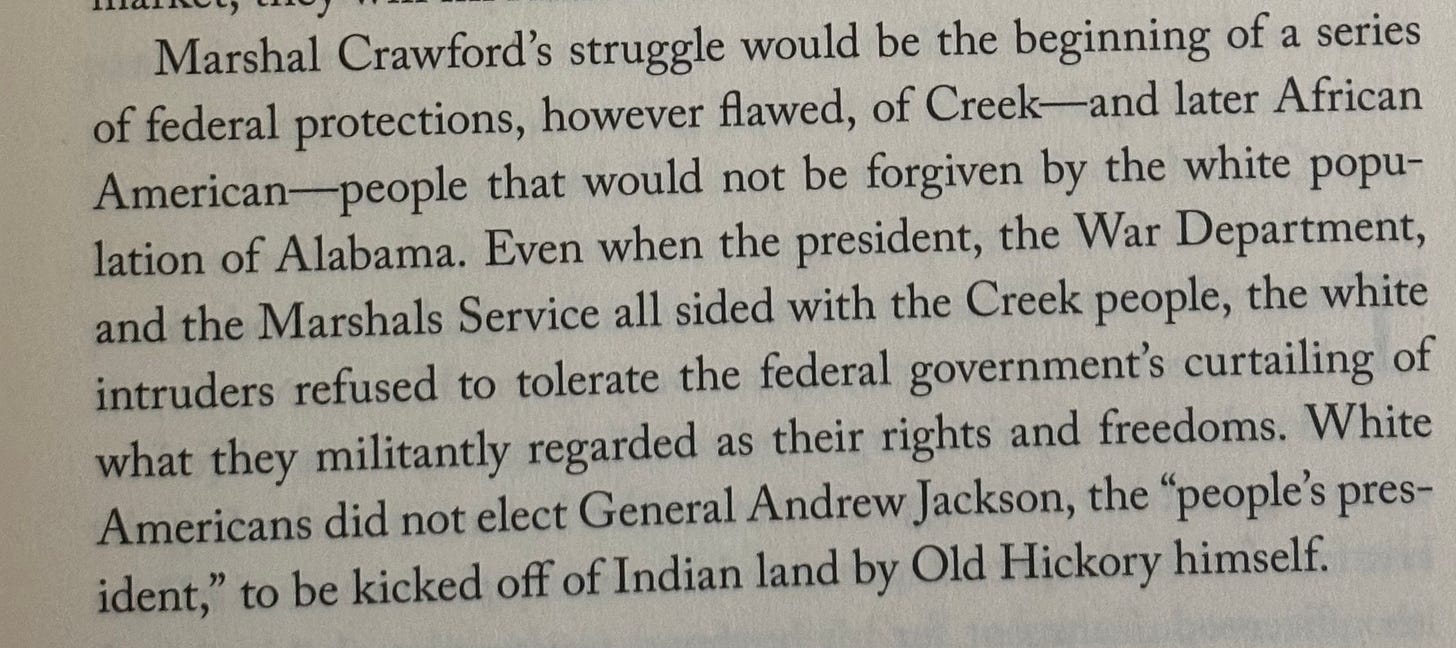

To be sure, Cowie keeps trying in his book to stretch his qualified and limited statements into evidence of flawed federal benevolence:

But those “federal protections, however flawed” can’t help but collide with “he was dead set on Indian removal as his eventual goal.” The protections weren’t flawed — they were temporary and tactical. The federal government wasn’t siding with the Creek people, who were a very few years away from being removed and sent west by the same federal government.

My view of Cowie’s highly regarded book is that his evidence undermines his forced and politicized argument. But the narrative cotton gin of a discussion with Anne Applebaum — a machine that relentlessly strips meaning and nuance from evidence — makes even a flawed argument much, much, much dumber. The Atlantic is an alchemist’s laboratory, turning gold into dross. Or, I guess, turning copper into dross.

The subtext underneath all of this discussion screams so loudly that it barely counts as subtext. A book about stupid, backward white people cruelly resisting the wisdom and benevolence of the wonderful federal government appeared in 2022 because Orange Man Bad. Read the reviews: they’re about how Jefferson Cowie’s history of Creek Indian removal in the 1830s shows how mean Donald Trump is. No, really:

Seeing the similarities between the actions and rhetoric of 1830s land speculators, 1870s Bourbon Democrats, and 1960s segregationists only further emphasizes that the rise of Donald Trump was not a break with American conservatism, but a manifestation of some of its longest-held traditions.

By the most remarkable coincidence, the one big lesson of the 1830s, the 1870s, and the 1960s turns out to be HARRIS / WALZ 2024. The Trail of Tears was totally like a Trump thing and stuff.

What a thoughtful meditation on the subject of the American past.

Is there nothing progressives can’t hitch to their Mango Mussolini hatewagon?

Well, at least we'll have The Trail Of Queers (classical sense peeps....:=]) if Harris wins..