In 1894, coal miners in southern Colorado joined a larger “marching strike” that did just what it sounds like: they marched. Pursuing a shift from isolated job action to a strategy of mass mobilization, thousands of miners left their own worksites and moved, en masse, to others, rallying other men to join their cause. They rolled a snowball, turning some striking miners into many — by walking around and talking to people.

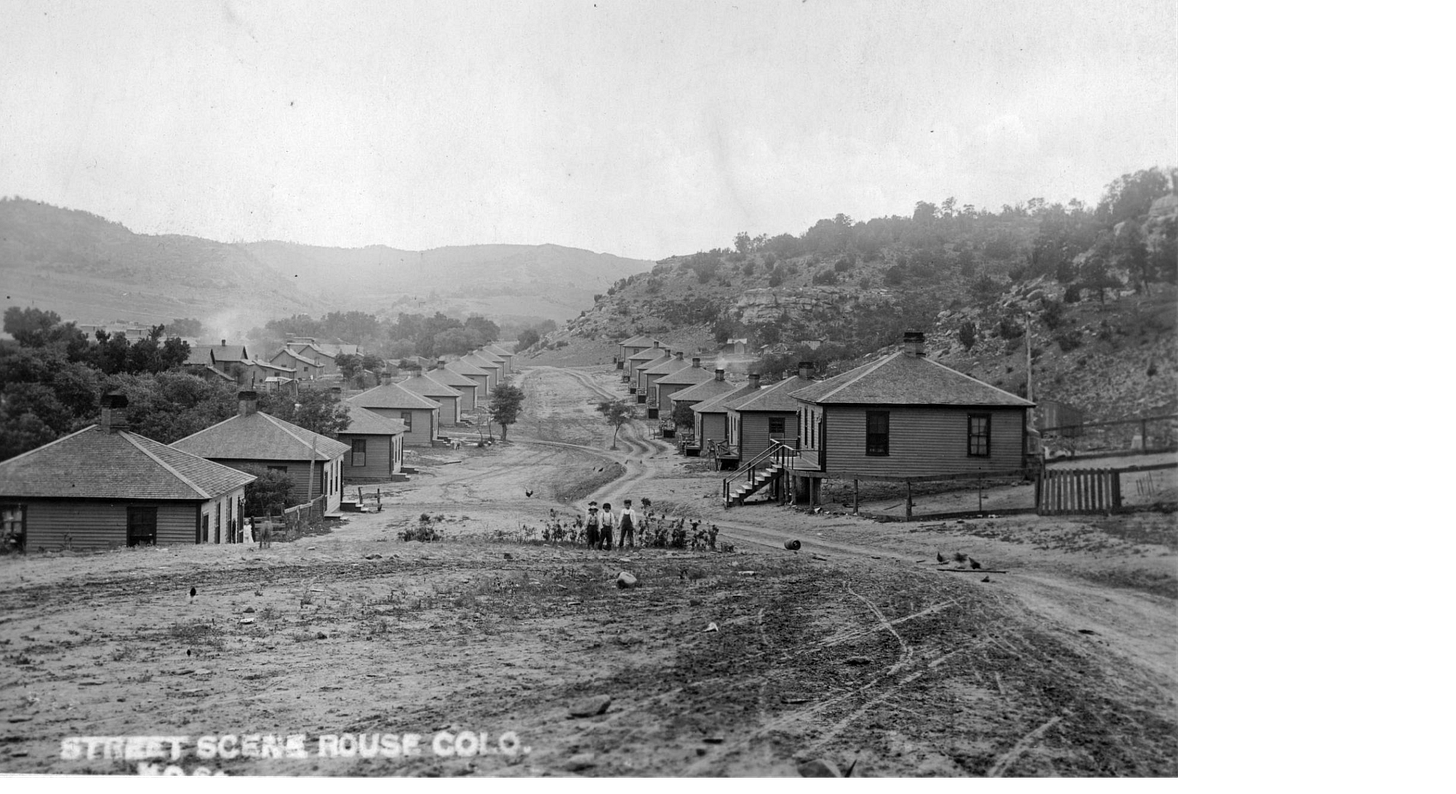

They were able to reach other miners and rally them through mass outdoor meetings in good part because of the way coal miners lived in southern Colorado in 1894. Mining companies paid them to come to work, and then miners drawn to a particular mine largely built their own homes and neighborhoods nearby. Others — sometimes mine widows — built independent saloons in those neighborhoods, places where miners could gather and speak freely. On the march, masses of laborers reached other masses of laborers gathered in their own neighborhoods, in space under their own control — in the language of social science, vernacular neighborhoods, spontaneous and uncontrolled, rather than tightly organized political neighborhoods. Mining towns were messy, lacking clean grids and common architectural styles; immigrant miners from different places built adjacent homes, Tyrolean huts next to adobe shacks. For Colorado coal miners, going home meant leaving company space and entering a place that they controlled. And then a bunch of other miners marched up and said that hey, we need to talk, and game on.

Recognizing the implications of self-managed miner neighborhoods, mining companies in Colorado did what mining companies did in many other places. They did this:

They built tightly managed company towns. Miners lived in company housing, shopped in company stores, drank in carefully operated company lounges (that sometimes encouraged them to try coffee or tea instead of the demon alcohol). Company towns were contained, with marked boundaries and company guards. The paternalism of the gift to miners — we’re going to improve your benefits and give you affordable housing that the company will build for you! — was a strategy of control. The next marching strike would encounter gates watched over by company patrolmen. Problem solved: no more access, no more labor action. To secure their control, mining companies poured money into local political contests, and so in effect surrounded mining camps with public officials — like sheriffs — who were company loyalists, and a de facto second layer of camp guards.

In his highly regarded labor history of the Colorado coal mines, the historian Thomas Andrews describes the the unintended effects of the effort by mining companies to isolate and control their workers. Miners saw the trap. They saw that their employers had seized control over every aspect of their lives. They understood the meaning of the effort to isolate and control them, and subsequently felt isolated and controlled. And so a maneuver undertaken to end organized labor action led to more organized labor action:

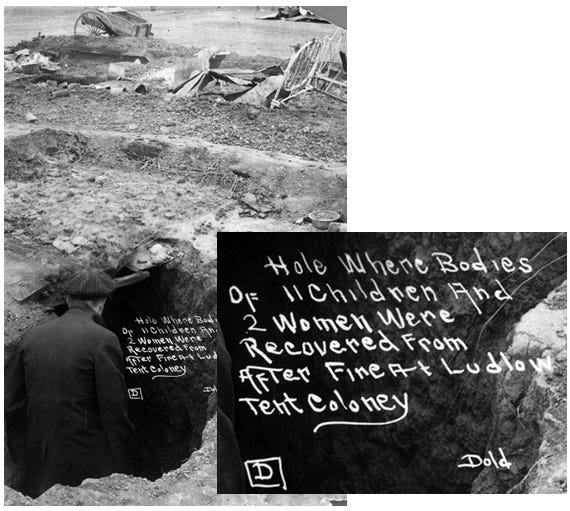

What Colorado Fuel and Iron’s new leader failed to grasp, then, was that miners continued to want the same things they had always wanted: safety, fellowship, a higher quality of life, autonomy, dignity, and basic freedoms. The paradox of prophylaxis was that instead of confining the struggle over such issues to the workplace, closed camps actually exacerbated conflicts between miners and managers. By making home, community, and electoral politics the key battlefields in the struggle for control of the coalfields, companies unwittingly transformed disputes rooted in subterranean landscapes into an all-out struggle in which the very meaning and fate of America seemed to hang in the balance.

The result was the Colorado coalfield war of 1913-1914 — “the bloodiest labor dispute in US history” — which included the Ludlow massacre and the resulting ten-day war. A conscious and explicit effort to control people and limit their political and economic options, to foreclose the possibility of organized labor action, led to an explosion of conflict.

In our own moment, a deliberate and increasingly aggressive effort seeks to contain political disagreement and narrow the public sphere. The President of the United States explicitly calls for social media companies to limit who will be allowed to speak publicly about our ongoing pandemic — and companies promptly comply, unpersoning the president’s targets. Banks suddenly close the accounts of politically controversial people and companies, or threaten to. An emerging social media competitor wakes up to find itself deplatformed by a giant corporation run by a politically connected billionaire. Professors are fired, or targeted for cancellation, for holding unpopular views. Employers police the speech of employees outside of work. Banks, not having been asked, report their customers to the FBI for using debit cards near the Capitol on January 6. And influential fools call for the government to install “guard rails” on our discourse, limiting what people are allowed to read, write, and say in the name of preventing authoritarianism.

The effort to assemble societal prophylaxis against unpopular views — or, rather, against views unpopular among a set of overlapping status groups who regard themselves as having the cultural authority to make decisions on what views should be regarded as improper — is loaded with paradoxical goading and provocation. People who feel themselves being pushed between those guard rails to protect our discourse, who feel open society and free-ranging media turning into a set of walled gardens surrounded by guards, don’t become easier to contain.

Your Twitter account is closed for “misinformation,” your Facebook account is suspended for wrongthink, and HR would like to speak to you right away. Every aspect of your life feels increasingly unfree. Does this make you calmer?

Does it quiet you down?

Love the prose. This question about nonviolent vs something else is what we are all asking.