"The Paradox of Preservation": Luxury Beliefs and the Future of the Dangerously Scenic Portion of Rural America

in three parts

One:

I got to Point Reyes on Sunday afternoon, and stopped to ask for trail information from the woman behind the counter at a National Park Service visitor center. It was a brief discussion, and not at all one that I thought of as an interview, but I asked her along the way if she knew when the ranches would be cleared off the land. Hard to say exactly, she responded, but it’ll be a big job out there, because they’ve got all these trailers for the ranch hands, so the park service will have to haul away a bunch of single-wides.

I didn’t fully notice what she’d said until later that day, when I was in a crosswalk in the nearby town of Point Reyes Station and looked up to see the front end of a BMW SUV coming straight at me. The driver managed to stop, but if you’re ever wondering where the Chris Bray Memorial Crosswalk would have been, it’s at the intersection of Shoreline Highway and 4th Street.

A minute later I was taking my chances in another crosswalk, up toward the library, and I paused to wait for a Mercedes SUV. On the way back down the street, I realized I was watching a kind of German SUV parade, with Audi and Porsche joining the others. The trailers will be the easiest part of the job of clearing ranches from Point Reyes National Seashore; the very old houses and the big barns will have to be torn down, if the decision isn’t made to preserve some of them as historical sites, while the trailers can just be loaded up and rolled away. But the presence of trailers is the thing that people mention when they talk about getting rid of the ranches, and it suddenly made sense to me.

When I talked to the Point Reyes rancher Kevin Lunny in Point Reyes Station the next day, I went looking for the SUVs again — but the Monday morning mix of cars had mostly shifted toward Hondas and Subarus, with a scattering of pick-up trucks. We sat in front of a feed store, drinking coffee, and had to stop every few minutes as locals — distinctly tending to the elderly — stopped to tell him how sad they were. One woman told him she was shocked to find out that the ranches were being ejected from Point Reyes National Seashore, not realizing that the fight had gone that far. “The rest of us kind of went to sleep,” she says, “because we couldn’t believe it.”

It was an accident, but my pictures frame Kevin Lunny, a longtime cattle rancher about to be thrown off his ranch, with the front end of a Range Rover.

The Press Democrat, the daily newspaper in the much bigger inland city of Santa Rosa, just published the first story in a series about the lawsuit and settlement that will lead to the eviction of the ranchers from the national seashore after 170 years. The Nature Conservancy is funding that settlement, and here’s one of the paragraphs from the newspaper about the way they did it:

Making the rounds in the affluent Marin County enclave of Ross on Jan. 12, 2023, they stopped by the house of Dan Kalafatas and his wife Hadley Mullin. He is chairman of the global climate strategy company 3Degrees, and she is senior partner and senior managing director at the private equity firm TSG Consumer Partners. Together, they agreed early on to support the cause and to help fundraise and spread the word to their well-connected friends.

Exactly.

“There is a shift,” Kevin Lunny says. An agricultural community is moving in a new direction; local school enrollment is declining, and the Catholic church in Olema is half a parish, sharing a priest with another church in another town. “THE PARISH IS EXPERIENCING A SEVERE SHORTAGE OF OPERATING FUNDS,” the church website says. The Lunny family is one of the dozen families who still worship there.

Point Reyes is becoming a place that’s visited. “Now there’s a lot of interest in visiting the seashore, right?” Lunny says. “It’s really becoming more an enclave of weekend homes.”

As they prepare to leave their historic Point Reyes ranch, the Lunny family is looking for other pasture land — a place to move their cattle, so they can keep going. I ask Lunny if they’re looking here, nearby, in the area around West Marin. He shakes his head. “Out here’s impossible,” he says. “It’s out of reach….Wealthy folks have purchased ranches for far above ranching value.”

Rural gentrification and the importance of environmentally sensitive private equity funding lead Kevin Lunny to a conclusion I started thinking about before I met him:

“It’s not about the natural resources. It’s about the people. It is. They want us gone.”

Two:

The purity of nature, frozen by management.

The Nature Conservancy’s announcement of the settlement celebrates the coming re-establishment of the native ecosystem. Farmed cows gone, wild elk welcomed across the newly fenceless park, coastal habitats restored — returned to what they were, before human hands and agricultural production reshaped the landscape. But in the same breath, the announcement says that the return to wild nature reflects an “improved management approach.”

A bunch of employee profiles at the Point Reyes National Seashore website describe the government scientists who will manage the nature:

So you see, when the ranchers leave, the lands will become untouched and authentic, in a return to the wild and the natural, guided by the managerial vision of a government agency and its staff scientists.

The term “the paradox of preservation” comes from the environmental historian Laura Alice Watt, a longtime observer of the battles over land use at Point Reyes. (The last battle, twelve years ago, shut down the Drakes Bay Oyster Company, which was also owned by the Lunny family.) Watt describes preservation as an act of construction, a behavior that makes new things from the choice to lock nature into supposed stability. “Preservation” isn’t invariably preservation. She sees the landscape as an “interaction of people and place.” So what does it mean to eject the people to preserve the landscape? The distinction between shaped and unshaped landscape, grazed land versus land managed as wild, opens a set of questions that are remarkably hard to answer.

As I’ve noted before, a recent op-ed essay in the local Point Reyes Light describes the effect of that choice: where other ranches have already closed, “the park’s non-management has allowed the landscape to be overtaken by thistles and tall weeds.” The wild landscape of restored ecosystems is tall weeds, depending on who you ask. The land will be managed, but one of the management choices will be to not manage it, guiding the re-emergence of the wild by not intervening. You see why Laura Watt started thinking about paradoxes.

When I stopped at the big Point Reyes National Seashore visitor center to ask about trails, I was looking for a way to hike through park land grazed by cattle — so I could see it myself, as a first thing, before I talked to anyone about it. I ended up driving to the end of the L Ranch road, then parking at the gate and walking the last mile-plus down to Marshall Beach. I made new friends — who came out to watch me pass on the trail, and shuffled along behind me for a while:

This next piece is my video, and it’s only 26 seconds long. It starts with the camera facing cattle-grazed ranch land, then crosses the gated road to the barbed wire fence where ungrazed land begins.

There you have the whole debate about the restoration of the natural ecosystem in a pair of contrasting images, the interpretation of which will depend on your own ideological priors. Is it good or bad? Is the ungrazed landscape authentic?

Whatever it is, this landscape will burn, and the park service knows it will burn. These signs are scattered around the park:

The first ironic outcome (which I’ve already noted) is that the National Park Service, knowing that the landscape will burn, is planning to rent cows to graze on Point Reyes after it evicts the cattle ranchers who currently pay rent to the government. The Nature Conservancy’s announcement acknowledges this point, saying that “targeted grazing will continue to be an important tool to achieve ecological management goals related to wildfire risk mitigation, weed abatement and wildlife habitat management on the Seashore.” They’re going to replace the cattle grazing with cattle grazing, because the land needs it.

The second irony is that the National Park Service has very proudly announced its post-ranching plan for the management of the land, explaining that park officials will be partnering with the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria “for natural and cultural resource protection and stewardship, use of traditional ecological knowledge, education, research, revitalization of community and tradition, and the overall stewardship of park lands and places.” The traditional ecological knowledge that native people applied to the stewardship of Point Reyes, before they were driven off the land by Spanish settlers in the 1830s, was fire. They burned it.

What this will mean in practice for the park service and its partnership with traditional ecological knowledge remains to be seen.

Kevin Lunny sees the paradox clearly: People who object to the presence of cattle ranches on the beautiful landscape of Point Reyes, demanding that cattle be removed to protect that landscape, are reacting to the beauty of a landscape that has been shaped by cattle. I took this picture on Monday afternoon, from the parking lot for the Point Reyes lighthouse, looking out across a big piece of the park’s pastoral zone:

All of that rolling green landscape is cattle-grazed land. You’re looking at a landscape that ranches have occupied for 200 years — Mexican ranchers since the 1830s, American ranchers since the 1850s. The National Park Service is going to remove most of the ranches, to preserve the land.

The questions about pure nature and native ecosystems go on, and I won’t be able to exhaust those questions here. You’ll find this tunnel of Monterey cypress trees at Point Reyes National Seashore, leading to a historic maritime radio station in the middle of the pastoral zone:

Planted in neat lines by human hands, they aren’t a product of the natural ecosystem; they’re an unmistakable result of the intervention of people on the landscape. No one is suing to remove this tunnel of trees and restore the wild landscape here, because visitors find it pretty.

Three:

On Monday morning, my attempt to get breakfast in tiny Inverness Park, up the road from the entrance to the national seashore, ran into a modest complication at the only store:

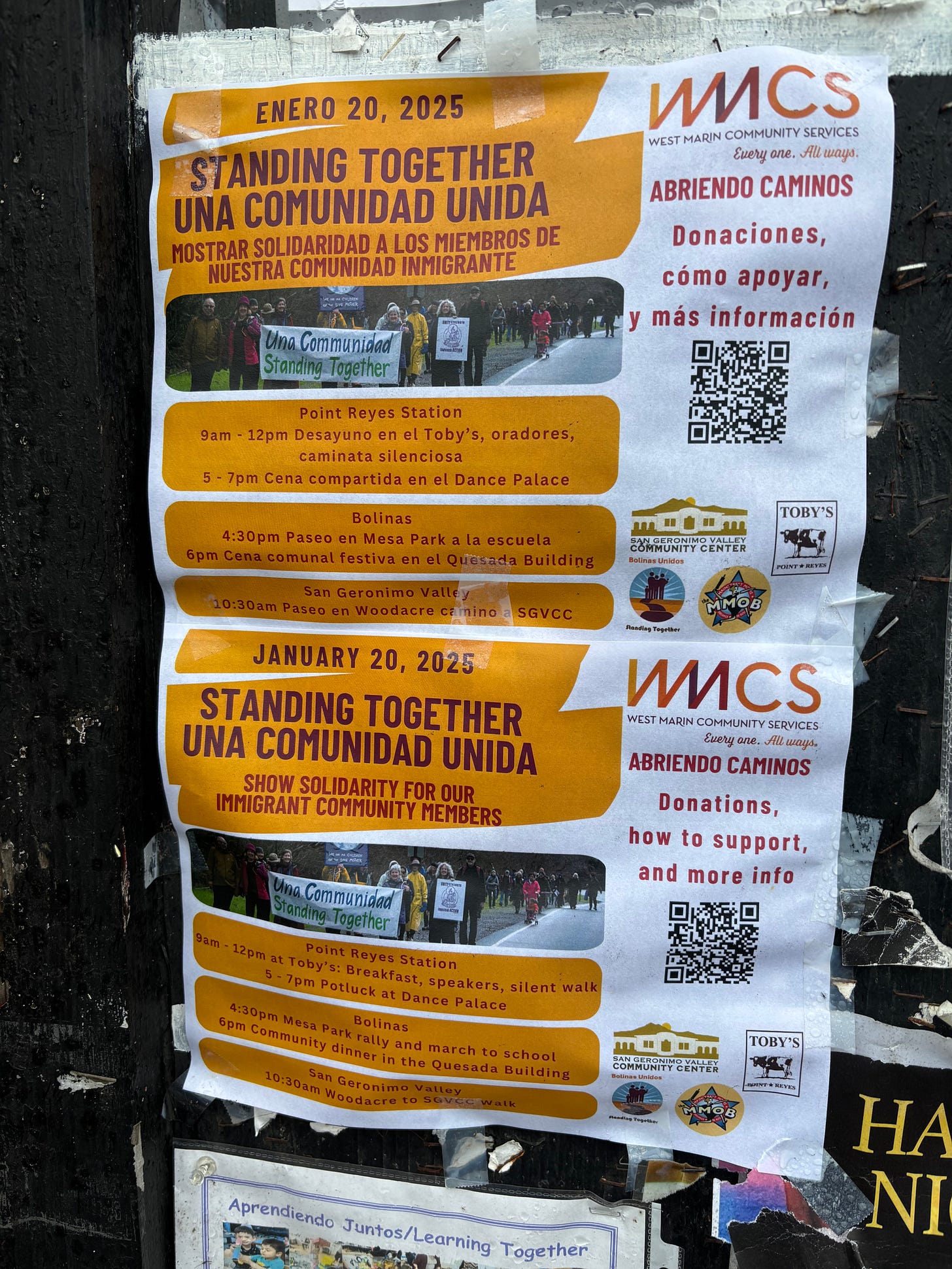

This is West Marin, like all of Marin. They had the immigrant march a couple weeks before the immigrant strike.

In a place where just about everyone is on the left, the conflict over ranching at Point Reyes is distinctly left-on-left: progressive ranchers with a long interest in sustainable and organic agriculture, with local support, versus environmental groups with private equity money from a little farther down the road toward San Francisco. In practice, these clashing progressive views views get tangled up in the divergence between performative politics and what people think about stuff in their own neighborhood, and the deep support for immigrants runs into a poorly masked distaste for Mexican ranch hands who live in trailers. You can read a distinctly left-facing take on gentrification and ranch labor here, in a piece that examines the end of ranching on Point Reyes through the lenses of race and class.

But the moment is bigger than the place, and reaches well beyond the local political scene. The argument that public lands should only ever be public — that is, that they should never be used for the private profit of usurpers like cattle ranchers — is a national argument, raised in Nevada against ranchers like the Bundy family who use Bureau of Land Management grazing leases. Anti-livestock environmental activists have been raging at "welfare ranching” for decades. For a local example, see this comment from my last post on the controversy, from a public relations professional in Mill Valley who warns against sympathy for the ranchers: “Had they cared for the land they claim to love as if it were their own, it might not have come to this.” This view is not only held in Mill Valley, and the victory environmental groups have won on Point Reyes will be replicated.

“It’s a belief system that no one should be using public land for private profit,” Kevin Lunny says. “And that’s a belief system you just can’t crack. But are they a majority? And should their belief system rule?”

That question will not be evaded.

Nature Conservancy might not be funding the fight against the ranchers for too much longer if their money comes from USAID…

"...opens a set of questions that are remarkably hard to answer."

Oh no, this is much easier than you realize. Have you never chatted with a city planner? They have a vision - be it urban core, urban periphery, suburban, whatever their specialty happens to be, and it is the enunciation of a particular aesthetic. That aesthetic encompasses everything, including people, as long as those people conform to the aesthetic vision of the planner. None of this messy, real human beings doing things not in accordance with the vision.

This is the Professional Managerial Class, and it surprises me not at all that parasitic management consultants (particularly one with "climate strategies") have the hubris to shape every thing they might touch, again in accordance with their vision/aesthetics.

This is my class, and I despise them with more passion than they deserve. As I note on my own 'stack - I am a proud class traitor.