Boycotts can build political connections, and have.

In 1754, prominent colonists like Benjamin Franklin thought the creation of a governing alliance between the British colonies in North America would lead to a more coherent response to political and military challenges. A few of the colonies agreed to discuss the Albany Plan of Union, but no one ever bothered to implement any of it. Different colonies, built on different economic, religious, and political foundations, had different cultures; they weren’t the same people, and had no basis for the creation of unity.

Somehow, though, just over two decades later, Massachusetts colonists killed the king’s troops in battle — and the other colonies rushed to join in a common cause, sending men to serve together under the command of a Virginia gentleman appointed on the basis of his mediocre military record. Colonies that couldn’t even begin to unify were suddenly able to promptly unify, though they remained weak on execution. Then, a year after that, colonies that had refused to make common cause in colonial affairs joined together to explicitly declare the formation of a new country.

1.) We have no shared identity or interests beyond a connection to the mother country;

2.) We’re all Americans.

Twenty years.

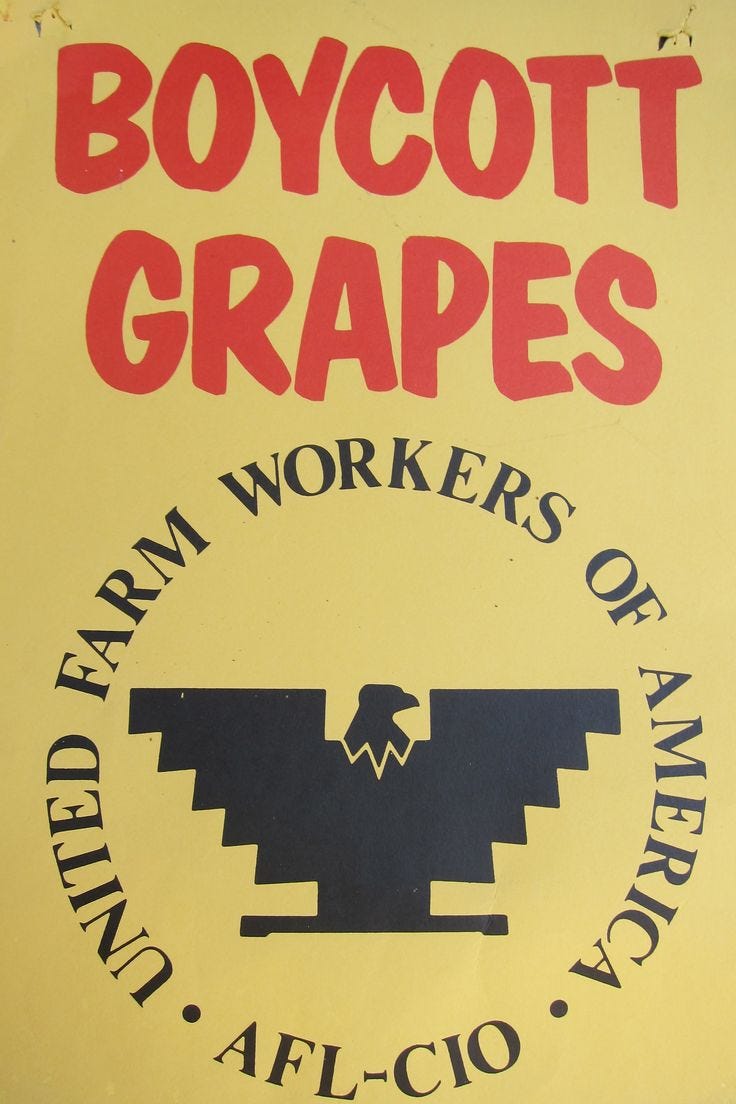

There are many reasons why the colonies developed the ability to unify around a shared cause and a common identity, but the historian T.H. Breen makes an important argument about the first place that colonists began to plan and discuss political responses across boundaries: the marketplace. Responding first to the Sugar Act of 1764, then to the Stamp Act of 1765, and then to the Townshend Acts of 1767, American colonists protested the economic and regulatory exploitation of the colonies by refusing to buy luxury goods imported from the mother country — the primary source of those goods at a time when the colonies exported raw materials and imported finished consumer products. A non-importation movement led to non-importation agreements and non-importation associations; a consumer decision became organized politics. The Sons of Liberty were born to boycott.

“By 1773,” Breen writes, “the mere possession of British imports signaled possible disloyalty to the common cause.” That’s two years before the first shots were fired. Here’s a typical version of the rhetoric of non-importation, from a Boston newspaper:

Our enemies know very well that dominion and frugality are closely connected; and that to impoverish us, is the surest way to enslave us. Therefore, if we mean still to be free, let us unanimously lay aside foreign superfluities, and encourage our own manufacture. SAVE YOUR MONEY AND YOU WILL SAVE YOUR COUNTRY.

The shared cause of refusing British goods, Breen writes, solved “the problem of the distant stranger,” allowing people to link their identities and efforts to the lives of other people they didn’t know. People in Connecticut weren’t buying imported luxury goods from the mother country; neither were people in South Carolina. They were the same to at least some created degree, sharing a cause. A boycott in the diverse American colonies made Americans. The implications pointed at action, at what people were willing to do. “I laugh at a man who talks of facing cannon and red coats, who cannot conquer his foppish empty notions of grandeur,” a Boston writer argued. Consumer choices demonstrated political discipline.

In our own moment, nothing yet has quite become a boycott, a term that implies organization and some degree of attempted enforcement.

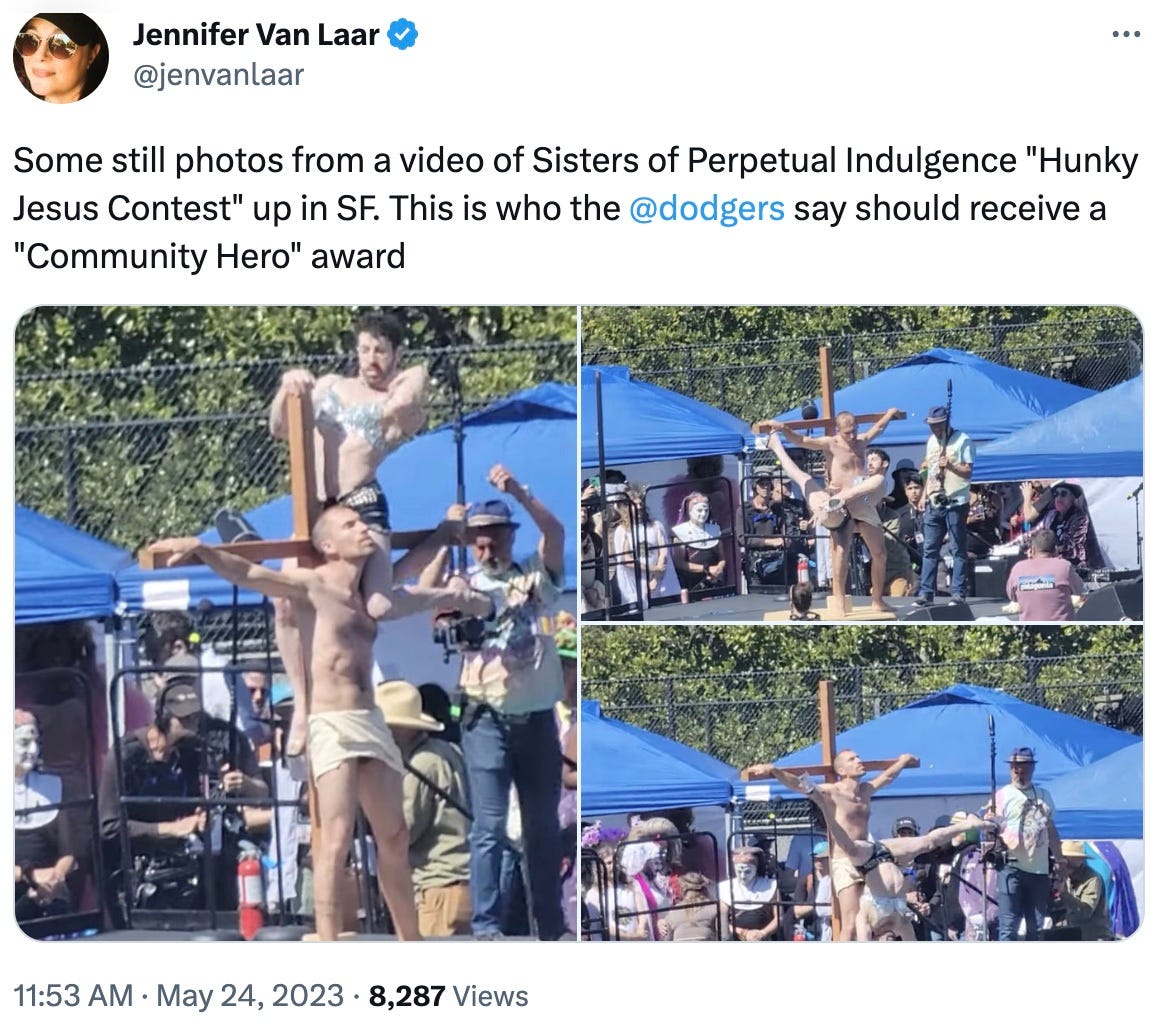

Widely shared sentiment against brands like Bud Light, with some goading from social media influencers, is more of a dramatic shift in consumer choice than a declared political action. But we’ll see. A first shift toward organizing the consumer pivot would be an declaration declaration of principles and intent. Boycotting The North Face because they put rainbows on some stuff strikes me as weak sauce; boycotting the Dodgers because they host and honor the “drag nun” group that does “Hunky Jesus” pole dancing with the principal symbols of a religious faith….

Yeah, boycott that.

A boycott of, especially, national corporate brands — conscious, organized, working toward defined ends on the basis of explicit principles, with groups and leaders consistently rallying people to a clear cause — could have significant political effects, bridging the cultural schism between the country and its willfully insane governing class. The principles will work best if they’re narrowly drawn, starting with “don’t sexualize childhood” and “don’t demean religious faith.” Resolute and widely shared insistence on those very directly stated cultural expectations would be powerful, and long overdue.

Save your money, and you’ll save your country. Or at least we have a shot at it.

And I really encourage anyone who wants to dig into the politics of consumer culture to pick up a copy of TH Breen's "The Marketplace of Revolution."

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-marketplace-of-revolution-9780195181319?cc=us&lang=en&

I couldn't care less about North Face's bearded lady or rainbows everywhere, and I don't think I'm alone. I find it silly, but *shrug* so much about modern America is silly.

I've tried to figure out what about the Dodgers, Target, and Bud Light made the difference, but I think it has something to do with the horrid imbalance of power. Dylan Mulvaney insults women every time he does one of his girlhood routines, but "misgender" him and he's crying crocodile tears and saying that using the wrong pronoun should be illegal.

Target put the sexualization of children front and center because they don't think people would notice as they try to up their ESG score by catering to a group that is threatened by the very idea that what they're doing they might have a right to do, but only be the grace of the rest of us as we don't see it as healthy or natural. As one person I read recently said (it might even have been you), how on earth do you reconcile the body positivity movement with let's lop off body parts to cosmetically change you into a stereotype of the sex you're not. It doesn't work. There is also no way to explain a "tuck friendly" bathing suit without a lot of awkward conversations about anatomy. (Trust me, I can't even wrap my head around "tuck friendly." WTH?)

Finally, you can't draw a picture of Mohammad, even a flattering one, without backlash for offending Muslims. In a majority Christian country, saying Merry Christmas is a microaggression. But the Dodgers can invite and honor a group that's very existence is dedicated to the twisting and mocking of the cherished beliefs of millions of people.

And that is in the end the sum of it: you cannot ask for respect you yourself are unwilling to give, and you don't hide behind kids to validate your own fringe ideas about sex and gender, and you don't give quarter to those who do.