Rough Men, Strange Peace

using an old moment to think about a new one

Donald Downard was not a nice man.

As one of his sons, who never met him, wrote in his memoirs, “I knew one thing of Lt. Colonel Donald Ephraim Downard— that he was a bad guy and that I should not be like him. It was drilled into me and my brother, David, like a jukebox on repeat, a daily reminder that I came from spoiled stock.” Later in that book, digging into family history, the author concludes, “As it turns out, my brother and I were not the only children he had, or the only ones he walked out on.” The total: six marriages, nine abandoned children.

In the spring of 1951, Downard argued with one of those many wives in the parking lot outside the officers’ club at Fort Monroe, Virginia. He was drunk, and so was she, and he had seen her talking to another man; after he called her a bitch and a whore, she slapped his face, and he dragged her into his car by the hair. Then he drove away with her — but she wandered back into the officers’ club later that night, alone, her hair "in disarray," her dress dirty, her stockings torn, her shoes gone, her face and body bruised and scratched. The officer in charge of the club sent for a doctor, who carefully cataloged her injuries for a crowd of MPs.

The resulting court-martial was not the only one Downard would face during his army career. In this instance, the army struggled to apply the law to his offense, because he’d beaten his wife under the Articles of War — just before the adoption of the new Uniform Code of Military Justice. Trying to make sense of the moment, the court convicted him under the old law but sentenced him under the new one, a procedural choice that would eventually cause the Court of Military Appeals to discard the sentence.

Beyond the problem of the law, though, the members of the court-martial had already been disturbed by the possibility that Downard would be forced out of the army because of the conviction they delivered. Arriving at a sentence they thought they were compelled to deliver — stripping Downard of his commission and throwing him out — they recommended that the convening authority disapprove their own decision. They urgently wanted Downard to remain in uniform, despite a trial that featured detailed testimony about his long history of adultery, unpaid alimony, dishonesty, and what the Army Board of Review would delicately call “domestic irregularities.”

How could they have wanted that?

Soldiers wear a ribbon on their uniforms to represent each medal they receive; subsequent receipt of the same medal is marked with an oak leaf cluster worn on the ribbon, rather than with more of the same ribbon. Donald Downard wore the Purple Heart with four oak leaf clusters — he’d been wounded in combat five times, receiving medical treatment and immediately returning to combat. Merely shooting the man wasn’t enough to stop him from continuing to fight. Here’s the citation from Downard’s Silver Star:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Lieutenant Colonel (Infantry) Donald E. Downard (ASN: 0-337997), United States Army, for gallantry in action while serving with Headquarters, 2d Battalion, 222d Infantry Regiment, 42d Infantry Division, in action on 25 April 1945, near Donauworth, Germany. In the attack on Donauworth, Colonel Downard was commanding a group of armored and infantry forces known as Task Force Downard. When the task force met heavy resistance, he mounted his infantry on the tanks and flanked the enemy by entering the town from the east. In this maneuver, Colonel Downard, disregarding his own safety, rode on the outside of the leading tank in order to control the attack and observe the tactics of the enemy. Through his outstanding courage and professional skill, Colonel Downard played a major role in the destruction of the enemy forces, the capture of the town and the subsequent crossing of the Danube River.

He instinctively led from “the outside of the leading tank,” the position of greatest danger.

Famously, Downard was present for the liberation of Dachau, and dragged the only survivor out of the train parked near the gates with over two thousand bodies stuffed into boxcars. In a moment of horror, confronted with death on a massive scale and the odor of closely packed decaying bodies, he jumped into a rail car and dug into the pile, then threw the one survivor over his shoulder and ran for help.

So in 1951, during the Korean War and the Cold War, less than two years after the first successful test of a Soviet nuclear bomb, a panel of army officers looked at a fellow officer and saw a disaster of a human being — drunk, violent, dishonest, a serial adulterer with a habit of domestic violence — but they also saw a brilliant leader, a man without fear or the tendency to hesitate in moments of savagery and horror. They saw a wreck, and saw that they needed men like that wreck on the inevitable battlefields of the very near future. Soldiers in a moment of war, emerging from another war and facing the possibility of several others, they saw the value of an uncommonly courageous warrior alongside the harm he caused in peaceful settings.

There’s also a good chance they saw a man who was understandably not at peace — who had come by a reckless and disordered personality the hard way, with what we would now call untreated PTSD. A court made up of the veterans of a war was inclined to show mercy to a well-known veteran of some of the worst combat of that war. They didn’t approve of his behavior — they voted to convict, as other officers would again at another court-martial — but they declined to discard him.

I opened several drafts of a book with this story, and got back every version with that opening quietly crossed out by an editor who hesitated to open a book we wanted to sell with somebody beating the shit out of his wife. I understood the marketing decision — imagine somebody flipping through the first pages at their local Barnes & Noble, right? — but the story said something I meant to say about the complexity of judgment and the relationship between warriors after the darkness of a war.

Donald Downard appears to have found some degree of peace, by the way, and his grave suggests that his sixth marriage stuck — after twenty years of struggle and darkness.

So.

Picture an infantry battalion in the US Army today, in a country that was at war from the late months of 2001 until August of 2021. Everybody but the noobs is a combat veteran; all the old NCOs and field-grade officers came up through this:

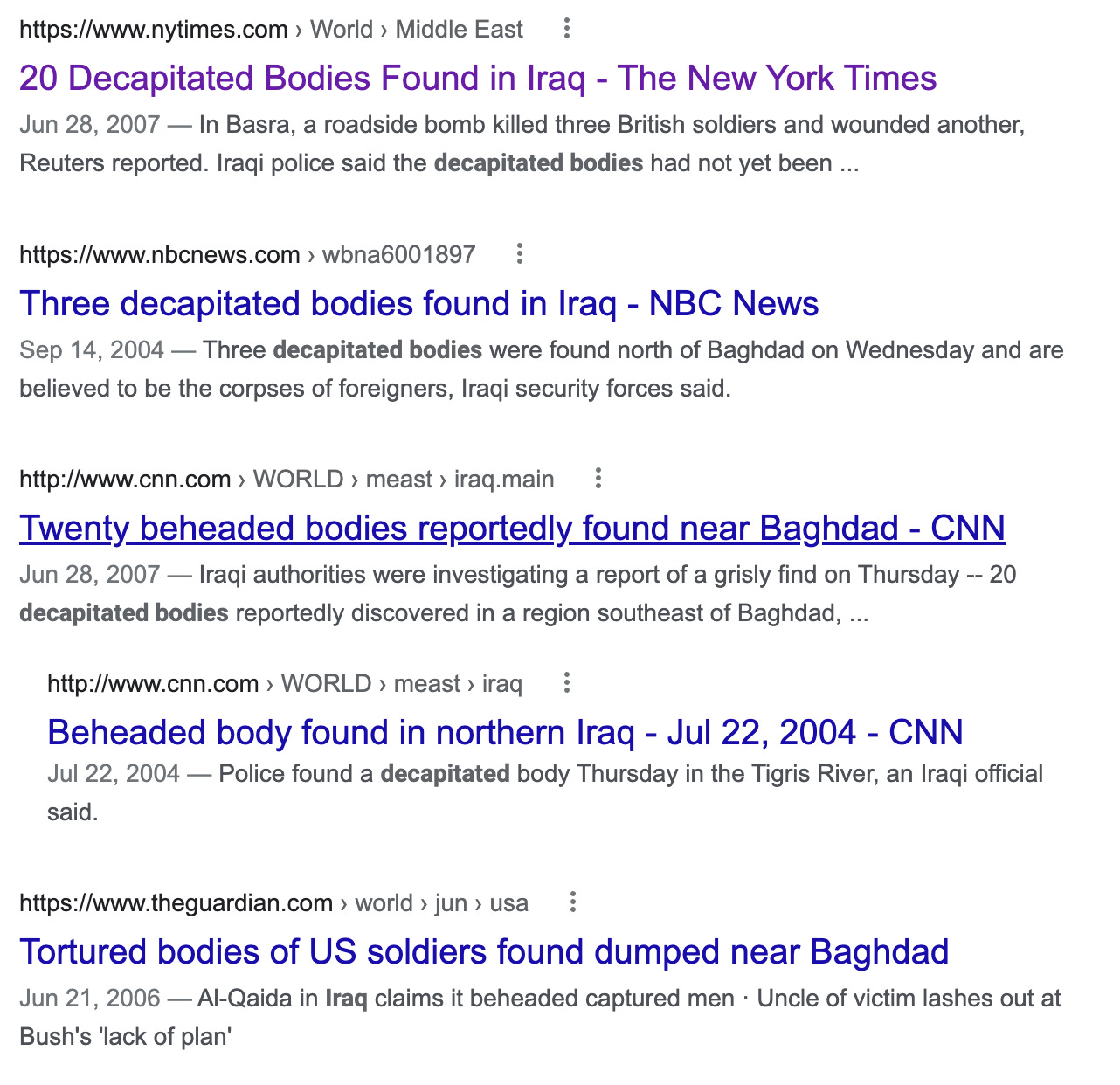

Try to put yourself in this position, unless you’re already in it: Imagine spending twenty years at war, in a setting of mass torture and ISIS beheadings, and then starting an instant transition to the new Biden-era military:

Twenty years of enculturation in the habits and practices of a wartime military, and then the sudden 180 into full-time proggie kulturkampf. Current top issue: Where will the troops get their abortions?

Add to this the appalling reversal of fighting for twenty years in Afghanistan and then walking away with nothing accomplished, leaving the Taliban to take over the whole country. And then add this:

Imagine the cultural collisions happening inside the combat arms fields today. And imagine what the American military looks like in five years. My best guess is that institutional culture doesn’t turn this hard and fast without breaking.

Had an ancestor who was reviled for being a wife-beating drunk. Everyone hated him, grew up hearing only about what an awful piece of shit he was. Later found out he was a cavalry NCO on the front in the Great War (hmm, wonder if that was related to the drinking?), and volunteered to fight in WWII (he didn't end up going; the officer in command recognized him and pulled him out of the ranks at the last minute, promoted him to warrant officer on the spot, and held him back to train the men).

Stories like the one you told here hit me in the feels. There's no respect for warrior culture in our feminized society and warriors are treated abhorrently. Homeless vets dying of drug ODs while migrants get free housing, education, and health care. Hysterical women destroying the careers of blooded line troops because they used the wrong pronoun or didn't want the Fauci Ouchie. Political appointees in generals' uniforms wrecking the lives of real officers because the latter called out the formers' mendacious incompetence. The shitshow of imperial collapse is a sight to behold.

Mr. Bray-

Wow.

I was shocked by the very first sentence. Dismayed at the next several paragraphs, and thankful to you- not for an apologetic of the man I called dad, but for unwinding the truths about the complexity of the father I knew.

Was he the perfect example for this article? No. He was the imperfect example that was perfect for this writing.

I am a product of Col Downard's final marriage- a tough, but happily successful one that he remained in until his death. To this day, I still have not met all my half-siblings.

And no apologies from me either. I do understand the path of broken hearts, broken homes, and broken families he left behind. But that is not the man I grew up with. Still Hard? Still Unrelenting? On the surface- absolutely. I grew up as his personal Private. And yes, he was a man that was truly haunted by his demons- prone to drink too much, set in his ways, and yes, to the very end, prone to hit the floor at the unexpected sound of a car backfiring as it passed on the street. He was, I know now, the textbook case of undiagnosed PTSD.

He spoke little of his military career. What I learned of his career, I learned from his men- both from WWII and Korea. And that's when I saw the hard man soften. Where I could see the "heart behind the hardness". Where I saw men like his company surgeon and others under his command, years later, talk with fondness, respect, and even reverence about his leadership- how they lost so many, but would have lost so many more without him at the lead. How they would follow him into hell again if asked. It was then that the flawed man I called Dad began to transition into my example of what a leader should be. My biggest regret still to this day is that I was too young to really appreciate it then... to comprehend it... and to thank him for who he tried to become. His lessons still resonate with me daily. I got to see both sides of the man and I thank "his soldiers" that reflected that brighter side of him.

As a follow-up to your article- after his medical retirement from the Army, he continued to fight for veterans. He joined the DAV and continually fought for the rights of those men and women- from WWII through Vietnam, helping them get their disability benefits from the government. He loved what he did. He was good at it. Why? Because he considered them all his soldiers and advocated for them relentlessly. To be sure, it took its toll. Their stories, their tribulations, brought back the darkness. He helped them because he "knew" them, he got them, he was them. In a way, he continued to lead "his men" until he retired- and it continued to shape the man, for better and worse.

He wasn't "bad stock" (although I understand where the sentiment originated). He was a product of his environment, and it had a significant impact on those that came in contact with him- for better on the front lines, and for worse on the home front. I pray that those with the same scars can relate, and can get the help that was not available to my dad.

I understand the intent of your article and appreciate your insights and how you applied his story to the "transition" that the military is going through. More than that, I appreciate your willingness to see, and tell the story of, the whole man.

Thank you.