Reality is Non-Binary

israel vs israel vs the palestinians vs the palestinians vs everybody else

The US Army was busy with other things during the Civil War, and generally unavailable for extensive military action against native people. In the burgeoning territory of Colorado, that reality meant that settlers in remote areas faced frequent and deadly raids from Cheyenne warriors, and smaller numbers of Arapaho, who wanted to roll back a growing population of white settlers. In the absence of effective federal protection against constant attacks, the territorial governor did two things: He negotiated with Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders who were willing to settle peacefully under the supervision of the small army garrison at Fort Lyon, taking themselves out of the fight in a way that could be monitored and verified, and he assembled a force of Colorado volunteers to find and attack the native bands who were raiding white settlements.

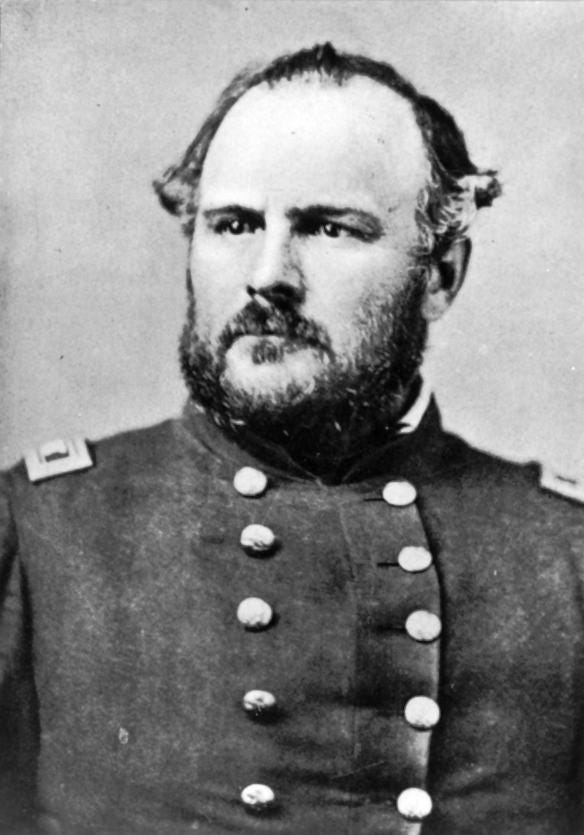

Infamously, the volunteers simplified their task by attacking the peaceful settlement that had agreed to live under army supervision. Under the command of the “fightin’ preacher” Col. John Chivington, who liked to put his pistols on the pulpit as a defiant message to any son-of-a-bitch who might dare try to stop him from spreading the word of God, the 3rd Colorado attacked the encampment on the morning of November 29th, 1864, killing hundreds of people who had explicitly declared their peaceful intentions.

The details are the familiar stuff of the Plains wars, with volunteers killing unarmed women, children, and the elderly as they tried to run and hide, and taking body parts as souvenirs. You can visit the place where this happened, Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, which I’ve mentioned before; you get there by driving through the unincorporated community of Chivington. There’s not much there but the Quakers, who leave their meeting house unlocked in case a passing stranger needs shelter.

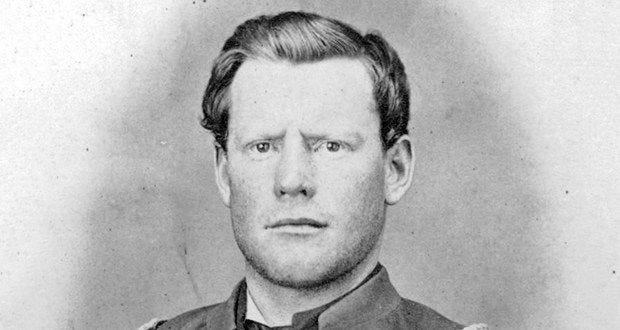

The volunteers of the 3rd Colorado weren’t the only soldiers at Sand Creek. Elements of the 1st Colorado had joined Chivington’s command in the field, and were present as the shooting began — but they firmly refused orders to join the attack (at least in part because the colonel organized the attack in ways that exposed his troops to their own crossfire). Most prominent among them was Captain Silas Soule, who was a captain because Chivington had promoted him after the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Arriving at Sand Creek with experiential context, Soule had been present for negotiations between Colorado officials and Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders; he knew firsthand that the people being attacked had been promised peace in exchange for peaceful conduct, and he knew that they had explicitly taken that deal.

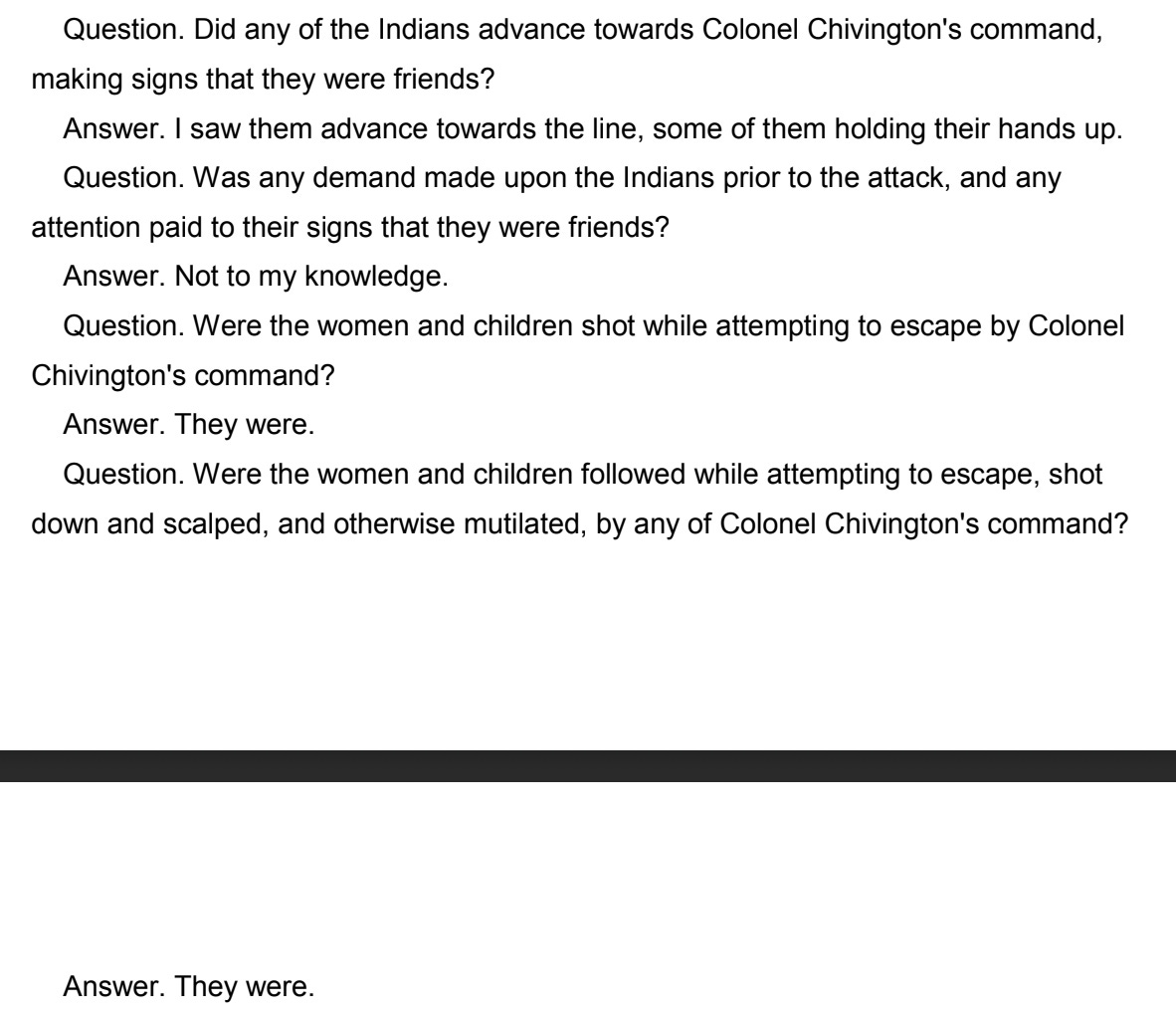

Soule was an abolitionist and (like Chivington) a Jayhawker, with considerable violence in his past. After the raid on Harpers Ferry, Soule had assembled an armed force to travel to Virginia and free Brown from jail, an effort he only abandoned when Brown sent word that he preferred to be martyred. You can read a good discussion of Silas Soule’s life here. He was a brawler, not at all shy about killing, but he declined to kill people who weren’t in the fight. After the massacre, he appeared before an army court of inquiry, offering testimony against Chivington in the presence of the commander he had defied:

A few months later, Silas Soule was murdered on the street in Denver — by a soldier of the 3rd Colorado, who wasn’t tried for the crime.

The American military disagreed with the American military. The long history of the American war on native people is riddled with ambiguity and institutional conflict, with different players providing different answers at different moments. The Dawes Act and the Trail of Tears are real parts of the historical record; so are the Indian New Deal and the return of the Navajo. Because the project of settling the presence of native people in a developing nation was practically and ideologically divided, it tacked and jibed rather than moving inexorably toward eradication.

And so native people persist, and their presence is written with great clarity on the maps of South Dakota, Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, among other places. The incorporationist American state proposed to remove native people, by varying means — by death, by relocation and concentration, by cultural reconstruction — but finally didn’t. Conquest and national consolidation are human processes, not flawlessly efficient political machines. Settler colonialism rarely eradicates; South Africa has a large black population, the Maori are culturally and politically important in New Zealand, and tribal sovereignty is a firmly established principle in American jurisprudence, though we continue to tack and jibe on the details.

So.

CJ Hopkins, explaining what’s happening in Israel:

Israel is a nation-state. It is doing what a lot of nation-states have done throughout the history of nation-states. It is wiping out, or otherwise removing, the indigenous population of the territory it has conquered. It has been doing this for 75 years. The indigenous population, i.e., the Palestinians, have been trying not to get completely wiped out, or otherwise removed from their indigenous territory, and lashing out at Israel in a variety of ways (i.e., from throwing stones to committing mass murder).

That is what is happening. The rest is PR. Public relations. Propaganda.

If you “stand with” the nation-state of Israel and its ongoing efforts to wipe out and otherwise remove the Palestinians from the territory it controls, I get it. The United States of America did that to its indigenous population. The British Empire did it in its colonies. A lot of nations and empires did it. It is standard nation-state behavior.

The United States didn’t “wipe out” its indigenous population, though the thought certainly occurred to a good number of Americans. “The British Empire did it in its colonies,” but postcolonial India is somehow not unpeopled.

Resist narratives about “standard behavior,” and notice the ambiguity that prevails in the current war between Israel and Hamas.

Israel assembled a force of hundreds of thousands of military reservists, and declared that a massive ground invasion of Gaza was coming; it hasn’t come. It may yet, but what we’re watching is debate within Israel about what comes next. “The nation-state of Israel” isn’t taking a standard action. Israelis are arguing among themselves, in good faith, on mixed evidence, about what happens next. I don’t trust any of the accounts we’re getting in the news, but they may be doing that because military leaders are concerned that Gaza is a trap, they may be doing that because they’re worried about committing too much force to Gaza in the face of a possible Hezbollah attack from the other direction, they may be doing that because Netanyahu can’t hold his political coalition together, and they might be doing that for a dozen other reasons. They are debating a course, a thing that people don’t do when they’re standardized instruments of unidirectional state power.

Similarly, Hamas is engaged in a long and grim battle for its place in the Palestinian political world. They came to power in Gaza in 2006, then decided that Gaza didn’t need to have elections anymore. The president of the Palestinian Authority is, at the very least, not a fan. This complicates the native people vs. the nation-state narrative from the other direction, since the native people aren’t a unified political entity, and never have been.

In the rest of Islamic Middle East, a supposed passion for Palestinian justice is slamming into a number of dark realities. Egypt responded to the Israeli attack on Gaza by rushing troops to the Gaza-Egypt border — to make sure the border crossing stays closed, keeping Palestinian refugees from escaping into the Sinai Peninsula. And the king of Jordan has just very plainly declared that Jordan and Egypt will accept no Palestinian refugees — zero, none at all, ever. So in the struggle between Jewish Israel and its Arab Muslim neighbors over the fate of Arab Muslims, the neighbors want….to keep their distance? There’s something happening here other than X vs. Non-X. Notice.

Returning to the framing of native people vs. the state, the Hamas attack on areas bordering Gaza reminds me of the ghastly end of the Modoc War or the attack on Fort Mims during the Red Stick War. Both produced aggressive retaliation, and both were devastating to the native people who thought they had delivered decisive harm to their enemies. Chapters followed chapters; events continue. Native people versus state power is about half the story. More will come.

The more I read, the more I want to stay far, far away from the entire debacle. No good can come from sticking our hands into that mess.

Typo fixed in the last paragraph, but you'll still see it in the emailed version.