Make It a Movement

In the Marketplace of Resistance

Make politics outside of politics. We already know how, and we’ve already begun.

The grim lesson of endless pandemic hysteria is that political institutions mostly don’t ride to the rescue. In Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, elected officials in opposition have sometimes nibbled lightly at the edges of prevailing policy, and sometimes jeered at elected officials in government for not locking populations down hard enough. In Canada, popular rage at the authoritarianism of Prime Minister Zoolander produced a snap election in which voters could instead support the nation’s Conservatives, who promised to…implement more or less the same vaccine passports that the left was enthusiastically preparing to impose. And in the United States, a few governors and the occasional attorney general have heroically made sense and resisted repressive policies, while legislators — well, I’m sorry, I missed it. If anyone knows of a legislature that did anything useful, send word. Uniparties are apparently a global phenomenon.

Political institutions mostly don’t offer salvation because they’re mostly occupied by symbolic performers who have swallowed a set of ritual obligations whole. They accept the prevailing premises of their status group as as givens. You can earn back some of your freedom with your obedience, if you promise not to use too much of it. Sounds good, right? An unremarkable claim advanced from totally uncontested premises.

But an answer to the failure of institutions can be found in the roots of the American Revolution. Not in the American Revolution, but before: in its origins and motive force. The answer to our political dilemma can be found in the late-colonial meaning of tea and other consumer goods.

You will, of course, know about the Boston Tea Party, but forget that for a moment. Start much earlier. In the wake of the Seven Years’ War, the British government was desperate to fund the obviously expensive burden of defending its colonies. They decided to fund the defense of colonies by extracting resources from colonists, in a series of tax measures that colonists vigorously resisted.

The political problem in colonial resistance was the disorder and disconnection of thirteen separate colonies, social and political units founded on different premises by different people under different circumstances. In the 1760s, people in North Carolina (say for example) didn’t regard themselves as being closely connected by common interests to the people of Massachusetts (say for example), and vice versa. Though they were all British subjects and all colonists in the Americas, people in Rhode Island didn’t particularly look at people in Georgia and think, “these are people who closely share my identity.” The thirteen colonies were thirteen colonies; the disunified colonists of 1765 couldn’t have fought the war against their mother country that began ten years later.

Nonimportation built unity, or at least the chance of it. After the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and the Townshend Acts of 1767 imposed taxes of a wide range of goods shipped into the colonies (and sharply limited direct trade between the colonies and the unmediated, untaxed world), colonists resisted tax policies implemented without their input or consent by declining the things to be taxed.

But they didn’t simply decline to buy sugar or tea as a personal choice; rather, they publicized, sustained, and enforced public demands for a coordinated refusal to buy imported goods subject to objectionable taxes. They made nonimportation a nonimportation movement, with nonimportation agreements and committees. Activists forced merchants — like the Boston merchant John Hancock, who later became better known for, I don’t know, other stuff — to decline British goods, even as it ate into livelihoods based on buying and selling. Colonists enforcing nonimportation as actors in an organized movement met coercion with coercion, and made a popular politics in social and economic settings.

The historian T.H. Breen argues that nonimportation forces us to “enlarge our sense of the political,” finding it places where people weren’t voting or only petitioning government. In the case of nonimportation, going shopping — or not — was politics:

In a colonial marketplace in which dependency was always an issue, imported goods had the potential to become politicized, turning familiar imported items such as cloth and tea into symbols of imperial oppression. And since Americans from Savannah to Portsmouth purchased the same general range of goods, they found that they were able to communicate with each other about a common experience. Whatever their differences, they were consumers in an empire that seemed determined to compromise their rights and liberties...

[And so] the colonists’ shared experience as consumers provided them with the cultural resources needed to develop a bold new form of political protest. In this unprecedented context, private decisions were interpreted as political acts; consumer choices communicated personal loyalties…

Commercial rituals of shared sacrifice provided a means to educate and energize a dispersed population…The non-importers of the 1760s and 1770s were doing more than simply obstructing the flow of British-made goods. They were inviting the American people to reinvent an entire political culture.

In our own moment, the decision to refuse submission to the premise that the body of a corporate employee is the chattel of the corporation, injected with experimental medications without the formality of informed consent in the manner of livestock or laboratory animals, is inescapably political. Refusing medical mandates for new and questionable pharmaceutical interventions, employees are asserting a demand for individual liberty that can’t help but speak to the entire human condition. Even if you make a choice for yourself, you’re stuck with it: we’re all in this one together. Politicians are explicit about their intent:

We’re obligated to reply with equal clarity.

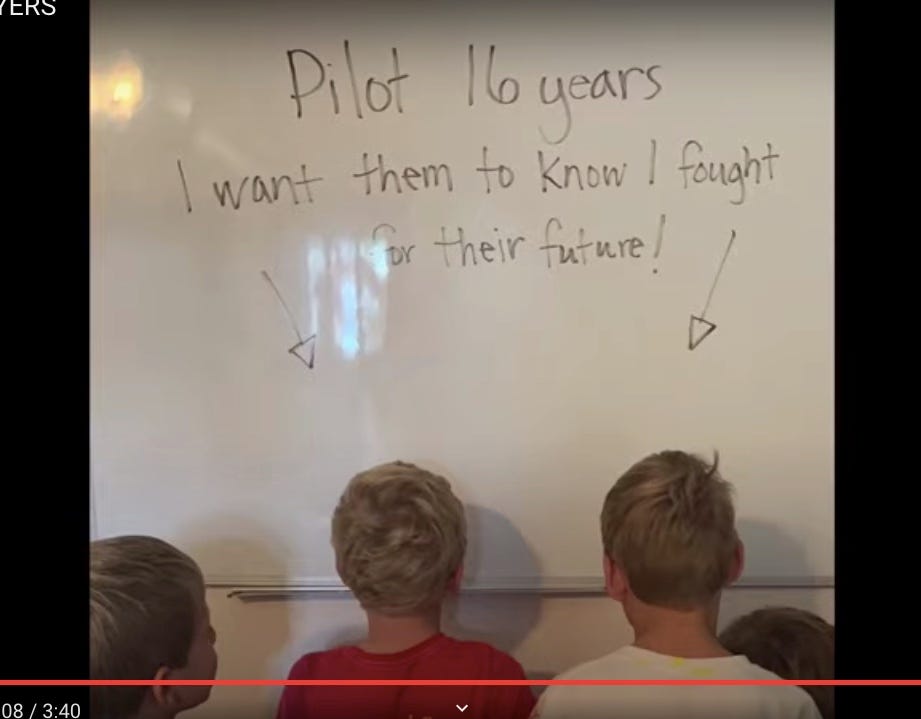

And so airline employees, for example, post a video describing their decision to resist the COVID vaccine mandate, in a series of moments like this:

This is politics. More specifically, it’s the basis of a new politics, one that routes around useless institutions. We can make our politics together, and it won’t have anything to do with elections or our political parties. Refusal needs to become a movement, with discussions across lines of geography and industry. Private decisions need to be interpreted as political acts, and offered as political acts. In the choice of personal refusal, we can invite the American people to reinvent an entire political culture. We have to, because the one we have now has failed.