Government Transparency: Dead

Murder, or suicide?

Try this where you live. It’ll take five minutes, and it’ll help you to see your local governments very clearly.

Last week, someone close to me was a victim of a strange and disturbing, but legally modest, local crime. The police made an arrest, and the person who was arrested was released a few hours later on a misdemeanor citation. Because the victim was someone close to me, because the crime happened where I lived, and because the person who was arrested was immediately released — and I’ve passed him in the street more than once in the subsequent days, in a small town in the Los Angeles suburbs — I looked up his court records.

This is a quick task I did at my kitchen table, through the website of the Los Angeles Superior Court. I immediately saw all of the usual things: arrested many times, convicted many times, usually for misdemeanors but also for a couple of felonies. Sentenced to probation, probation, probation, probation, probation, probation, and probation, often being sentenced to probation while he was on probation. Another website and a one-minute search told me he’s spent a day or two in jail nineteen times — nineteen times. (He is just leading you down the primrose path!)

But then I saw something else: He had been arrested several times in the later months of 2019, and charged in late 2019 or the first months of 2020, but a string of cases stalled; even minor charges lingered in court for years. A chickenshit misdemeanor arrest in May, 2019 led to a procedural hearing in March of 2022. There are many possible explanations, but it made me wonder the obvious thing:

Are courts still overwhelmed with cases that stalled while courthouses were closed? Are judges currently buried in the 2020 slowdown? A recently updated news story says yes, but then adds this detail: “No one knows how many thousands of cases have been caught in the pandemic backlog.”

But hold on, I said, because we have ways to find this information. My local police department, probably like your local police department, publishes a detailed annual report on its website that lists how many crimes were reported to them, of what type, with a clearance rate broken down by category. There’s a table with numbers of calls, numbers of arrests, numbers of citations. This is what we did this year. It takes a few minutes to compare years, if you feel like something has changed.

So surely the courts and the district attorney’s office do the same kinds of reporting, right, and it would be easy to see if there was a sharp pandemic-caused decline in cases filed, or in criminal cases managed to a conclusion.

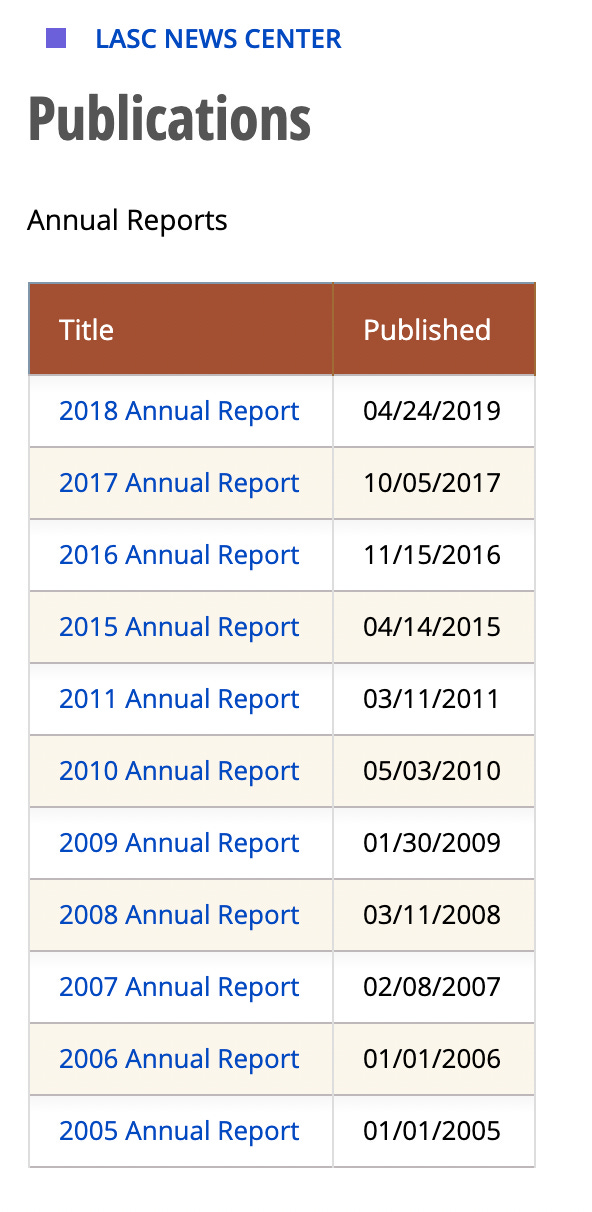

So. Here’s the annual reports page for the Los Angeles Superior Court, as it looks this morning — April 19, 2022, ladies and gentlemen:

Are you not entertained? Three years behind without a hint of an explanation or a promise of a timeline.

If you bother to go into that last annual report, for 2018, you’ll find that it tells you how many civil and criminal cases were filed in the report year. But it doesn’t say anything at all about how many were resolved, adjudicated to some form of completion. To compare the justice system to a slaughterhouse, cows get counted going in, but no one will admit to counting how much beef goes out.

The reports page for the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office offers one report on the office as a whole, “Year in Review 2021.” No reports for prior years are available, so there are no comparisons to make to information that they’re previously provided. With apparent pride, that report offers this fact, with a comparison you can’t check: “Public safety is the overriding priority of the office as shown by the almost identical rate in which felony cases were filed in Los Angeles County over the past three years. The office filed felony charges against 32,114 people between Jan. 1, 2021, and Nov. 30, 2021. They represent 51% of all the individuals whose cases were presented by law enforcement agencies to the office for criminal charge filing consideration.”

Half the time the police think they’ve caught a felon, prosecutors agree to pursue charges. Remember that if you ever get arrested in Los Angeles County, ‘cause you’ve got a coin-toss chance of not having to worry about it.

The DA’s filing rate is higher for misdemeanors, except that they give themselves a plate of measurement fudge: the removal of “addiction-related misdemeanors,” which the DA’s office no longer charges, diverting addicts to treatment without prosecution. That chart looks like this:

Though, of course, they don’t say how they figure out who counts as an addict, and what criteria they use to check. So, like, Harold and Kumar: they good, or does it have to be more?

As with the courts, then, we have a report of how many cases, or what percentage of cases is filed. The link’s above, if you want to check, but the thing that’s missing, again, is outcomes: What’s the office’s felony conviction rate, which should be extremely high after they weed out half the cases that reach their desks? If they don’t file charges against addicts, how many of the defendants who get their get-out-of-jail-free card actually report a completed course of treatment to the DA’s office? Shrug, don’t know. It’s pretty rare for a prosecutorial agency to not report its conviction rate, and it’s absolutely certain that they know what it is.

But surely the number is available somewhere, right? The DA’s office is funded by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, so they must get regular reports on the performance of an office that they pay for. Well:

Here are the complete results of a search on the DA’s website, and I’ve left some blank space at the bottom of the screenshot so you can see all the nothing:

Something that we talked about, once upon a time, but no longer, you know, a thing.

For most of my life, normal government included courts that offered some year-end data, and a DA’s office that told you how many convictions they won. In Los Angeles, we don’t have any of that anymore. Some cases were filed; various things subsequently happened. This is bad faith, an indifference to basic accountability, standing on the firm foundation of the correct belief that neither the Los Angeles Times nor the Board of Supervisors will bother to notice. And I promise you, as someone who lives here, this reality shows up in the streets, shitting on the sidewalk and checking your car door to see if you forgot to lock it.

It should take two websites — court, DA — to find out if you’re in the same boat.

Right. Now do the same exercise looking for mortality stats at your state/local health department. My state Maryland has yet to publish all cause mortality stats for 2020- that data was due November 2021.....the reason for this delay for these data sets is not provided, but one can speculate....

I bet they have a whole chapter in the annual report on Diversity and Inclusion.